Are Shamans The New Therapists?

Are Shamans The New Therapists?

The two shamans on my Skype screen aren’t exactly fighting for my attention, but they are as close to fighting as such spiritual practitioners are likely to get. John Germain Leto has just led me through a chakra meditation meant to align my energetic field—him giving instructions from his Laguna Beach, California, home to me in my New York City apartment. He has advised me to ground myself by feeling the presence and support of the Earth underneath me. At first it’s a little strange to breathe in long moments of silence with strangers on Skype. It feels a little rude, for instance, to close my eyes. But soon I get into it. I feel calm. I breathe deeply. I am quiet.

But as I open my eyes and Leto talks about the importance of surrendering control, his partner, Eden Clark, is fidgeting. She clearly wants to say something. “Eden has some things that are coming through for you,” he acknowledges, then continues to explain the rattles he used to open the session: He was journeying with my soul and clearing away some heaviness. He also sensed my power animal: a female cheetah. I’m suddenly proud of myself. That’s a kick-ass animal.

Finished, he cedes the floor to Eden. She finally pours forth with what she’s been channeling. Namely, she’s been chatting with my spirit guides, and they’re a little irritated with me. They know I’m ignoring them. “Acknowledge them,” she says, then goes quiet to listen more. “Let them in. Talk to them.”

She asks if that resonates with me. I have to admit that it does. The skeptical part of me wonders: Maybe she says this to everyone? Maybe we all tend to ignore our gut feelings and later regret it? But I’ve struggled particularly with this throughout my life. I even used to have panic attacks because, I am certain, I was in denial of what I knew: that I needed to move from Chicago to New York, that I needed to end an engagement, that I needed to embrace a new relationship. I’ve gotten better at letting intuitive guidance in, but there will probably always be a part of me that would prefer taking a book or a website’s advice over going on pure faith. It will likely be a lifelong battle for me, but something about hearing this from someone else renews my desire to keep trying to listen.

She nailed me, having barely known me. And via Skype, no less.

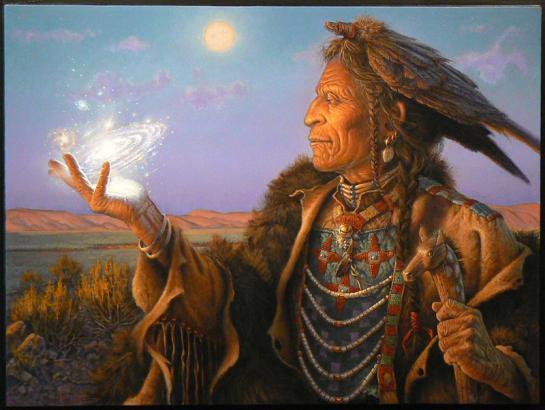

Clark and Leto are among the many shamans in America bringing modern sensibilities to an ancient practice. Shamanic approaches to energy healing—the use of drums and rattles, ceremonies that sometimes involve mind-altering substances like Ayahuasca or San Pedro (known as “plant medicine”), and, most importantly, communication with the spirit realm to solve earthly problems—have been around for tens of thousands of years, pre-dating the major world religions we recognize today. But shamans have been popping up in mainstream American culture with increasing regularity over the past few years, though exact statistics aren’t tracked. Author Elizabeth Gilbert visited one in Indonesia in Eat, Pray, Love. The “purging ceremonies” led by shamans—yes, the physical effects are exactly as advertised—using substances like Ayahuasca are all the rage, covered in the likes of the New York Times and Elle. These have also resulted in a few newsmaking deaths in places like Peru, where it’s legal; some stateside shamans swear by plants’ powers, while others use them sparingly or prefer rhythmic drumming as a consciousness-raising tool.

“Therapists are always like, ‘How do you feel about that?’ But people don’t want to keep trimming the sick tree every day. They want to know why this tree is sick and how they can make it better.”

Trendy mind-altering substances aside, it makes sense that shamans would be finding more acceptance, given the prevalence of other alternative therapies such as yoga, Reiki, massage, acupuncture, and meditation—once-fringe practices that are now slick, multibillion-dollar businesses nationwide. “The social climate on Earth is at an all-time high,” says Shaman Durek, a Los Angeles–based practitioner who pals around with the high priestess of alternative trends, Gwyneth Paltrow. “The pressure cooker is a little hotter than it usually is, so people are looking for ways to burn off steam, deal with these earthly anxieties they’re experiencing—what’s happening in politics, what’s happening with ISIS, what’s happening on a global scale.”

Those earthly anxieties combine with people’s ever-more-packed schedules and desire for greater meaning to create demand for a practitioner who can do it all: a little bit of therapy, a little bit of spiritual meaning, and a little bit of physical relief. That’s exactly what shamans promise. “Therapists are always like, ‘How do you feel about that? What are you feelings about this?’” says Durek. “But people don’t want to keep trimming the sick tree every day. They want to know why this tree is sick and how they can make it better.”

Seeking Soul Mates

Though modern American shamans use many methods to do this—and draw on a variety of indigenous traditions from Tibet, Korea, North America, South America, or Africa, among others—most of them spend some time talking about and working with energy and soul. That can take the form of energy-clearing, sessions aimed at connecting with your spirit guides and emotional release work. “We help people understand and influence their energetic bodies,” Leto explains. “And that’s not too far a stretch for most people these days: Dr. Oz is talking about the chakra system every other week on his show. More and more people are getting to know, Hey, I’m more than just this bag of skin and bones.” (I checked on the Dr. Oz claim; yes, Leto is correct.) Clark adds, “The beautiful thing is that no matter the tradition, the commonality is this concept of the soul. Shamans learn to read the soul, to understand the soul and how that influences all things in your life.”

Sounds great. So how do they do that, exactly? Shamanism is easy to talk about in grand platitudes but slippery to pin down in specifics, starting with how they identify themselves and who gets to call themselves a shaman. In ancient times, shamans would emerge among tribe members as their abilities became apparent. Word would spread: Hey, that guy cured my kid. Hey, that guy knew just how to settle a dispute between our two best hunters. Hey, that guy really calmed everyone down last night with his rattling and chanting. Hey, that guy helped me actualize my personal truth by giving me a power animal. So tradition dictates that one does not take on the shaman title, which is an act of ego; the shaman title just naturally confers itself upon those who are worthy.

Occasionally, that heavenly calling story still plays out. Durek, for example, has known since he was a child growing up in suburban San Francisco and Hawaii that he was meant to follow in the tradition of his great grandmother, an African medicine woman who was taken to Haiti and New Orleans as a slave. “When she was living, she told the whole family that there was going to be a boy who she would choose,” says Durek, who’s 42. “I started showing a lot of the shamanic gifts when I was 5. I started noticing that the things I saw were not what other people saw. We’d be playing outside, and I’d be like, ‘Oh, look, there’s this woman here and she’s telling us all these amazing things!’ And the kids would look at me like, ‘What?’ Then people started calling me a freak, and that’s when my awakening hit me: Wow, I’m alone.” With guidance from his mother, he learned to choose the right time to share his insights and the right time to keep them to himself, and as an adult, he began formally studying spiritual traditions throughout the world.

But in general, the whole let-the-village-decide approach doesn’t quite work in 2016 society. Websites and social media profiles demand word-based descriptions of one’s profession. And clients feel better if there’s some kind of certification system. Though no centralized system exists, several groups offer workshops and databases for finding program graduates, such as the Foundation for Shamanic Studies and The Four Winds Society (where Clark and Leto trained). “A lot of what is out there calling itself shamanism is not,” says Susan Mokelke, the president of the Foundation for Shamanic Studies, which has trained 50,000 students since it began in 1985. “We train people in authentic methodologies so they can access these other realities where the spirits live. Whether or not they’re an effective shaman is between them and their spirits. That’s why we don’t certify people as shamans.”

Translation: Those who seek help from a shaman must start with a certain level of faith in the process and trust their intuition in finding the right practitioner. And just as there are myriad types of talk therapy to choose from, shamans come in different forms, with varying approaches and modalities. Doug Sutton, for one, had long been a believer in the power of tapping into realms beyond the earthly one. He’d been immersed in personal growth throughout his career as a corporate consultant when he heard about Clark and Leto’s practice from his next-door neighbor. He joined one of their South American retreats and soon began seeing them for one-on-one work monthly, usually via Skype since he lives about an hour’s drive south of them in Encinitas, California. Since he began seeing Clark and Leto, he says, he’s less “weighted down” by stress and the lingering effects of bad relationships: “I have felt profound releases.” (Shamans call this “cutting cords.”)

New Jersey comedian Kate Wolff has unquestioned faith in her shaman, New York City–based Alyson Charles. “She isn’t afraid to get down and dirty with real life,” Wolff says. “She knows there’s always work to do, even on herself.” Wolff started seeing Charles to deal with what she describes as “toxic” relationships with men—one man in particular. But Wolff knew Charles was onto something during one session in which she simply shouted over and over at Wolff, “Just be!” As Wolff explains: “She kept yelling that at me. I wanted to yell back, ‘I’m trying!’ But there was nowhere to hide anymore.” Charles soon broke up with the problematic guy in her life and continues to see Charles regularly five months later.

A Higher Calling

In fact, breakups come up a lot in the modern world of shamanism. They’re common reactions for clients when they start working with a shaman—a clear manifestation of life change. They’re also common origin stories for practicing shamans: catalysts for taking on a new spiritual journey. Clark worked with a shaman on a plant medicine retreat in Peru before she had her own practice; when she returned home to California, she quit her job as a tech company executive and left her husband to pursue a spiritual path. Leto ended an engagement and left a job in New York as a modeling agent for music stars such as Beyonce and Usher. The two met during their training at Four Winds Society and soon realized, as they followed their own guides and intuition, that they were meant to be shamans, and to practice as a couple. “That’s one of the common things you hear: It’s not really a decision you make,” Leto says. “Spirit chooses you. You have to answer the call.”

Charles also left her fiancé and a high-powered job in TV production. “As I took steps for my own healing, those steps honored me back in showing me my own healing abilities,” she says. “That began this co-creative dance I’ve been on ever since.” After a few years of exploring different modalities and working with several shamans, including her aunt in Santa Fe, she “came out of the spiritual closet” three years ago with an Instagram post declaring herself, as she says, “a practicing public shaman. It was pretty terrifying. I knew that was going to be the game changer. You can’t go back on that.”

For Durek, too, positioning himself in today’s society proved complex. “I knew as I got older that I wanted to be able to communicate with everyone,” he says. “A lot of shamans I met were shamans in their region, and they based what they did on their knowledge of that region. I realized that I was born to be a shaman in the metropolitan lifestyle. How do I bring this hippy-dippy fairy-dust kind of information into people’s lives in a way that actually makes sense to them?”

That’s the challenge of modern shamanism: adapting ancient practices to an overstressed, technology-laden, cynicism-soaked world. Interestingly enough, anthropologist Michael Harner—whose 1980 book The Way of the Shaman helped introduce shamanism to Western audiences—actually describes shamanism in a way that sounds perfectly suited to our times: as a high-speed technology of sorts. “It’s a method of getting direct access to what people in other spiritual traditions only talk about,” says Harner, who founded the Foundation for Shamanic Studies after the release of his book. “In our ancient ancestors’ lives, shamans had to move quickly to help people who were in need. Being able to do that is a human ability that’s atrophied, and we’re restoring it.”

Our shamans don’t look or act exactly like their ancestors. “I think people connect with me because they see that, yes, I’m a shaman, but I wear hot shoes and nice pants,” Durek says. “I’m not dancing around smoking peace pipes.” And with such technologies as Skype and Instagram at these new shamans’ command, news of a cheetah spirit animal or angry spirit guides can zip instantly to us from across the country or the world—a development that would certainly blow their ancient predecessors’ minds.

by Jennifer Keishin Armstrong For Mind Body Green

Be the first to post a message!