Buddhist Ethics for an Age of Technological Change

Buddhist Ethics for an Age of Technological Change

We live at the apex of a long era of revolutionary change, with deep roots in history. This change has accelerated over the past centuries due to the technologies gained from empirical and scientific investigation.

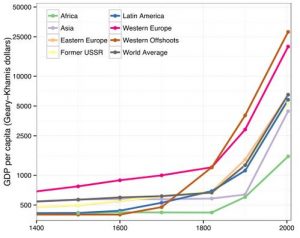

Our change stems from a process of increasing knowledge of our world, leading to an increasing effectiveness with which we manipulate it to suit our wishes. Perhaps the biggest evidence of this change is the precipitous growth in human population, life expectancy, and per capita income following the Age of Enlightenment.

Human population had been growing slowly for around the last seven thousand years largely due to improvements in food production, but life expectancy did not improve markedly until the 20th century due largely to improvements in public health, hygiene, and nutrition, which themselves correlate with improvements in per capita income. This led to massive population growth.

Economist Angus Maddison has estimated that per capita income did not grow markedly until around 1820 due to the “recognition of human capacity to transform the forces of nature through rational investigation and experiment”; that is, “experimental science”.

Another way to understand this growth is in terms of the efficiency of production. As economist Paul Krugman (1997:11) put it,

Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.

Improving productivity comes down to making technological advancements such that work that used to be done by two can now be done by one. Advancements flourished during the industrial revolution, with inventions such as the steam engine, machines for textile production, food production, transportation, and so on. Then research into the physics of electromagnetism in the 19th century led to the availability of distributed electric power in the 20th.

Recently we have seen what futurist Jim Carroll terms an “exponential growth” of knowledge. He points to recent advances in genetics and renewable energy among other things. This growth stems crucially from “Moore’s Law”, the regularity first remarked on by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore back in 1965, that the number of transistors on a computer chip doubles roughly every eighteen months. This regularity has persisted for over fifty years up to the present day, and is the basis for the exponential growth in computing power over our lifetimes, itself a catalyst for knowledge.

Improvement in transistor density is due to continual improvements in the performance of semiconductor manufacturing equipment, where photolithographers learn to use smaller wavelengths of light accurately to transfer more compact circuit diagrams onto wafers of silicon. (Van Zant 1997:11). Newest equipment works with light in the extreme-ultraviolet range, and research continues into X-ray lithography.

Much of the work in this field is on the bleeding edge of scientific and technical knowledge, and yet its success is the basis of all modern computing, from digital audio and video to computers and cellphones to the internet itself. It is also partly the basis for the rapid decline in solar photovoltaic system costs. (Taylor 2015:80).

Our rapidly increasing knowledge leads to an accelerating increase in impact: not only are we becoming more powerful as a species, each of us is individually becoming more powerful as we gain mastery over greater technologies. This may not be obvious at a glance, but think of the impact a single person could have nowadays with a gun, car, or explosive, much less an airplane. A person in ancient Rome had recourse to little besides a sword.

As methods for formulating and producing nanomaterials, including genetic materials, become more widespread, and as costs and complexities decrease, methods for the production of good and ill will become available to more. Performance and pricing of DNA sequencing technologies has followed a so-called “Carlson Curve”, much akin to the exponential Moore’s Law.

One does not need to believe in a “technological singularity” to see that this is a chaotic and potent process: each individual will be able to make a larger and larger impact.

Bill Joy, technologist and co-founder of Sun Microsystems, crystallized the problem back in 2000 when he discussed some potential dangers of genetics, nanotechnology, and robotics in particular:

Together they could significantly extend our average life span and improve the quality of our lives. Yet, with each of these technologies, a sequence of small, individually sensible advances leads to an accumulation of great power and, concomitantly, great danger.

What was different in the 20th century? Certainly, the technologies underlying the weapons of mass destruction (WMD) – nuclear, biological, and chemical (NBC) – were powerful, and the weapons an enormous threat. But building nuclear weapons required, at least for a time, access to both rare – indeed, effectively unavailable – raw materials and highly protected information; biological and chemical weapons programs also tended to require large-scale activities.

The 21st-century technologies – genetics, nanotechnology, and robotics (GNR) – are so powerful that they can spawn whole new classes of accidents and abuses. Most dangerously, for the first time, these accidents and abuses are widely within the reach of individuals or small groups. They will not require large facilities or rare raw materials. Knowledge alone will enable the use of them.

One may debate the extent to which Joy was right in worrying about these developments in particular, or about how long the dangers might take to materialize. In a 2008 update, Lucas Graves noted that doom had not yet descended upon us. And in their response to Joy’s article, John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid wrote that social factors (such as Joy’s own input) will intervene to mitigate any great damage from such technologies.

Anthropogenic global warming (AGW) is evidence enough however that human power and productivity has a potentially terminal downside. The role of a handful of oil barons in bankrolling anti-AGW propaganda shows how powerful and effective wealthy individuals can be.

Generally speaking, biological exponential growth tends to fall afoul of the Malthusian catastrophe when resources are exhausted. Any exponential growth is eventually unsustainable, and as they say, what is unsustainable will not be sustained, one way or another.

One tempting answer is to say that what is needed is more knowledge, better technologies. And surely that is not wrong. More knowledge about the effects of global warming might, for example, convince more people that it is real and that it might be uncomfortable. More research into methods of counteracting its effects, scrubbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, or other “hail-Mary”-type geoengineering projects might collectively make a difference in the medium to longer term.

But even so the basic problem will remain: we are individually and collectively becoming more powerful, by harnessing ever greater sources of knowledge. As technologies become more potent and available, their potential for mischief becomes greater.

The Problem: Knowledge and Wisdom

It isn’t so much that we need more knowledge, it’s that we need the right kind of knowledge. We need to be able to distinguish what is important from what is unimportant, skillful from unskillful, right from wrong, good from bad. That is, we need ethical knowledge, as part of the social factors that can influence technology development and adaptation for the better.

Now, it may be said that ethical knowledge isn’t the thing that can be taught or learned. It’s the sort of thing we either know without learning, or the sort of thing we effortlessly rationalize away. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt, following David Hume, has claimed that moral emotions and intuitions drive moral reasoning rather than the reverse. That is, when we look to decide what is important, skillful, right, and good, we look to our emotional responses to things. If some state of affairs elicits a positive emotional response, we take that as evidence that the thing is good; if negative, we take it as evidence that the thing is bad. Then we confabulate reasons for our subsequent moral choices.

While this does not quite establish that ethical claims are irretrievably matters of personal whim, at least it tells us they are epistemically problematic. And this matters, for in many cases involving basic human emotions such as greed and hatred, our emotional response may, at least arguably, get the moral facts entirely backward. For example, we typically decide that what is important, right, and good is that we accumulate as much as we can. (Greed). We typically decide that what is important, right, and good is that those people whom we dislike end up suffering. (Hatred). Indeed, we typically act to fulfill those very ends.

This picture of our ordinary way of thinking and acting fits precisely with the Buddha’s picture of the untutored mind:

n untaught ordinary person … does not understand what things are fit for attention and what things are unfit for attention. Since it is so, he attends to those things unfit for attention and he does not attend to those things fit for attention.

What are the things unfit for attention that he attends to? They are things such that when he attends to them, the unarisen taint of sensual desire arises in him and the arisen taint of sensual desire increases … And what are the things fit for attention that he does not attend to? They are things such that when he attends to them, the unarisen taint of sensual desire does not arise in him and the arisen taint of sensual desire is abandoned … (Majjhima Nikāya 2.5-6).

“Sensual desire” covers both our positive reaction to pleasant sensations (greed) and our negative reaction to unpleasant sensations (hatred). Or in other words, the untaught ordinary person takes those things to be most important which produce pleasant sensations and eradicate unpleasant ones. His ethical system, such as it is, revolves around the notion that what is important, skillful, right, and good is what feels pleasant to him right now.

Such an ethical approach necessarily leads to egoistic short-term thinking. It is unpleasant right now to undertake campaigns to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Those in positions of wealth and power, following the ethical program of the untaught, feel anger toward those things that are unpleasant to them, so they strive to eradicate anti-AGW programs. So too with issues of higher taxation: those of greater wealth gain pleasure by seeing the increase in their accounts. The idea that such an increase might be limited by taxation is unpleasant to them, which causes anger. They strive to eradicate the cause of their anger, so they fund efforts to end programs to raise their taxes.

At base this is an issue of getting the ethics right: of understanding “what things are fit for attention and what things are unfit for attention”, or in other words what is important and unimportant, skillful and unskillful, and so on.

It is an issue of gaining wisdom. Wisdom is not simply knowledge; it is not simply the gathering of facts. It is knowing which facts are important. It is knowing which facts to gather and which facts not to gather, since we have limited time and effort.

The aim of science is to gather knowledge. While knowledge is indispensable for wisdom (ignorant wisdom is an oxymoron), science alone cannot tell us what is important. We need wise understanding to guide us.

Learned Wisdom

The question is whether wisdom can be learned, or whether we are doomed to ignorance. This is not an idle question; on it may depend our future. As the amassing of scientific knowledge accelerates, so too does human power, for good and ill. If wisdom cannot be learned, then we will tend instead towards our unlearned, ordinary ways of thinking and behaving.

In his recent book The Better Angels of Our Nature, Steven Pinker presents data that violence has declined markedly over the past several centuries. He also argues that recent declines are due to the integration of Enlightenment ideals such as tolerance and human rights. If Pinker is correct, and his data is persuasive, it provides some substantial indirect evidence that wisdom may be taught and learned, even on a broad social level.

If wisdom can be learned, it probably cannot be learned by everyone, or under all conditions. One needs to be open to it, perhaps psychologically close enough to it in Haidt’s sense, in order to learn; and even then, learning may be slow.

So-called “Dark Buddhism” notwithstanding, I doubt there are many people who will go from Ayn Randian selfishness to selfless generosity and compassion. What is more likely is that we will understand an ethical position cognitively, assent to it as an abstract proposition, but find ourselves unable to live up to it in practice. In the West this is known as “weakness of the will”, in Buddhism “wrong intention”. If we can at least notice such wrong intention when it arises and strive to change, it may not be much, but it isn’t nothing either. It’s a start.

This isn’t so much a matter of learning to vote a certain way, or that global warming is harmful. In practice it may tend rather to amount to our learning to become less possessive, less greedy, less angry, less neurotic, less upset. These too are ethical issues insofar as they impact ourselves and others for good or ill. It may seem there is a vast chasm between a few people learning to be less angry and our being able as a species to deal with the accelerating power that information provides us, but change begins in small ways on a personal level.

If as the Buddha says in the Dhammapada,

Hatred never ends through hatred.

By non-hate alone does it end.

This is an ancient truth. (Dhp. 5)

then we must learn somehow to live through non-hate, difficult though that may be to our untaught, ordinary minds.

The scientific jury is still out on the extent to which any given practices can moderate greed, hatred, and other harmful emotions. However it is under active study. For example, psychologist and neuroscientist Kent Berridge and others are working on the neurological origins of desire and craving. Discussing this work, Peter Whybrow, director of the Semel Institute for Neuroscience at UCLA, laments that in some of our contemporary social norms,

We have yoked fundamental biology, putting wanting, liking and reward

together into a cultural vision of what is progress. We’ve forgotten how you constrain desire.

Berridge is pursuing techniques of meditation to aid in mitigating addiction, the deepest form of desire. This is only one of many parallel streams of investigation looking into the potential relation of meditative practice to emotional change. It is early days yet, and although data is promising it is far from complete.

Buddhism and the World

In its fullest elaboration, Buddhism is world-renouncing rather than world-embracing: since saṃsāra is necessarily unsatisfactory, since it is impermanent, suffering, and non-self, it is not something to which we should become attached. This approach has benefits in cultivating a less resource-intensive lifestyle: as we learn to renounce, we learn to need less. We learn benefits of non-acquisition that may counter our ordinary impulse to acquire.

However renunciation can also lead to a measure of what might be termed disengagement from issues of social and political justice, and might equally lead to disengagement from the technological issues already outlined. The danger is one of meditative practice leading to “narcissistic self-absorption” as Bhikkhu Bodhi puts it. As regards the recent turn towards mindfulness meditation he says: The great leaders of social transformation, both in theory and action, for the most part do not practice the meditative mode of mindfulness, and the foremost exponents of meditative mindfulness in a Buddhist setting hardly promote large-scale social transformation. Contrast for example the African American Christian clergy involved in human rights campaigns, or the Christian and Jewish clergy who have led the campaigns against US military involvement around the world, with the Buddhist meditation masters. The former, with perhaps a few exceptions, don’t practice meditative mindfulness, while the latter show only a marginal concern with social justice issues.

One might add that there were many secular activists involved in these social campaigns as well. (Jacoby 2004).

There are many confounding variables, involving the causes and conditions in which these various figures arose. One cannot therefore take any grand lessons from Bodhi’s claim, but it should give pause. Meditative insights are not a panacea, and if they are to be best used to social effect nowadays they will most likely have to be modified.

One modification prominent in contemporary Western Buddhism is the heightened prominence given to mettā (loving-kindness) meditation and the other Brahmavihāras, as compared to their relatively marginal role in the Nikāyas. Living in larger and denser communities today, we probably need more focus on kindness and compassion than those living in the scattered rural communities of 2500 years ago.

Another modification will be the integration of social, political, and planetary action into the dhamma, as indeed is manifested in Bhikkhu Bodhi’s own role in founding Buddhist Global Relief.

Those of us involved in the Secular Buddhist enterprise look to promote a secular approach to the dhamma, one more in tune with our contemporary scientific understanding of the world. But focusing on secularism cannot be our only goal.

Conclusion

Accurate information is not enough. Further scientific and technological advances may be necessary to overcoming our present difficulties, but they are far from sufficient if we are to flourish in the longer term. We also need to know how best to use increasing knowledge and power to our common benefit. We need to focus on cultivating wisdom.

In a recent article, economist Jeffrey Sachs argued much the same thing: that “We need both science and morality to reduce the risk to our planet.” Sachs, like biologist EO Wilson, has looked to ally himself with liberal and open-minded religious leaders, as well as those from the secular community of course, in the struggle to help save our planetary heritage. The stakes are too great for us not to put differences aside when our common future is so at risk.

It is essential to work together now. In the medium to longer term, we need to cultivate the acquisition of wisdom so as to stave off the time when our rising influence over the natural world might imperil us all. In his 2000 paper Bill Joy crystallized many of the potential dangers that accelerating technological change might bring. He also sketched out a possible route to betterment, interestingly along Buddhist lines:

Where can we look for a new ethical basis to set our course? I have found the ideas in the book Ethics for the New Millennium, by the Dalai Lama, to be very helpful. As is perhaps well known but little heeded, the Dalai Lama argues that the most important thing is for us to conduct our lives with love and compassion for others, and that our societies need to develop a stronger notion of universal responsibility and of our interdependency; he proposes a standard of positive ethical conduct for individuals and societies …

The Dalai Lama further argues that we must understand what it is that makes people happy, and acknowledge the strong evidence that neither material progress nor the pursuit of the power of knowledge is the key – that there are limits to what science and the scientific pursuit alone can do.

Our Western notion of happiness seems to come from the Greeks, who defined it as “the exercise of vital powers along lines of excellence in a life affording them scope.”

Clearly, we need to find meaningful challenges and sufficient scope in our lives if we are to be happy in whatever is to come. But I believe we must find alternative outlets for our creative forces, beyond the culture of perpetual economic growth; this growth has largely been a blessing for several hundred years, but it has not brought us unalloyed happiness, and we must now choose between the pursuit of unrestricted and undirected growth through science and technology and the clear accompanying dangers.

Scientific and technological growth are inevitable and largely beneficial in any healthy, open, modern society. They are a simple byproduct of people asking questions and looking to improve their lot. Hence we must act in whatever limited ways we can to mitigate their dangers. The ethical and practical guidelines of the Buddhist Path provide one promising method for bending the arc of change towards the skilful.

by Justin Whitaker For Patheos

Be the first to post a message!