The Mandala: Mapping the Cosmos and the Soul

The Mandala: Mapping the Cosmos and the Soul

Human civilizations are replete with approaches to portray or represent some aspect of the universe. Calendars, ordinary maps, star charts, and other diagrams are examples of methods of making sense of or map part of reality. The calendar is a way to understand time because the map is a way to understand geography. Even ancient temples were developed to be a model to make sense of the cosmos. One type of diagram or map is the mandala - that can be thought of as a map of reality.

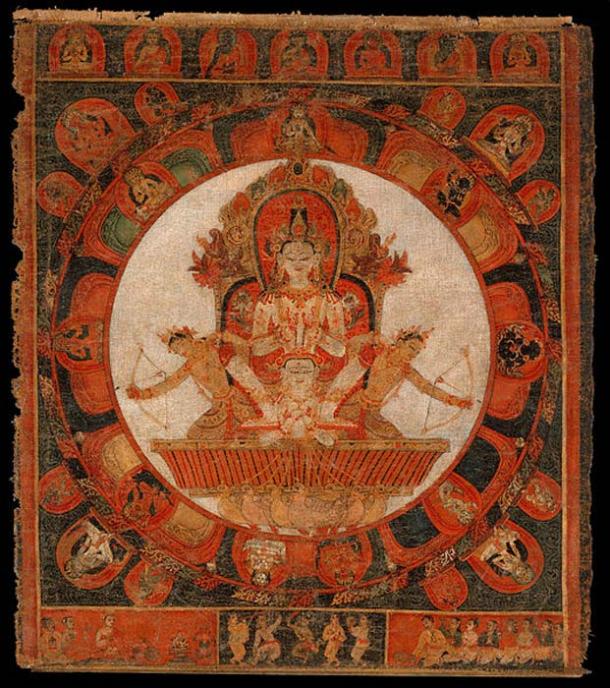

Mandala is a Sanskrit word that simply means circle. It is used within several Indian religions for meditation or to invoke the energy of a deity. Within Hinduism, a frequent sort of mandala is the yantra which normally depicts a circle with a deity with which it’s associated in its centre.

Mandala of Chandra, God of the Moon. Nepal (Kathmandu Valley), early Malla period. ( Public Domain )

Types of Buddhist Mandalas

An average Buddhist or Hindu mandala consists of a square with four gates representing the cardinal directions with a circle circumscribing it. The circle may contain elements that represent physical facets of the world like the elements (fire, earth, water, etc.) and may also have symbolism of a directly religious or spiritual nature

One Buddhist mandala includes an outer circle with flame symbolizing charnel grounds where corpses are left unburied to decompose. The inner circle in a square represents the bounds of the realm outside the samsara where gods and enlightened ones, or buddhas, reside. The realm out the samsara is the abode of those who have attained enlightenment and have broken free of the reincarnation cycle. The symbols representing the charnel grounds are supposed to remind people of the brevity of human life and how nothing lasts and to remember to not become overly attached to anything lest it lead to suffering.

Painted 19th century Tibetan mandala of the Naropa tradition, Vajrayogini stands in the center of two crossed red triangles, Rubin Museum of Art. ( Public Domain )

Another Buddhist mandala, known as the cosmic mandala, consists of a fiery red outer circle and an inner ring containing spiral lines. The inner circle of the mandala symbolizes the “first movement” of this world. Extending between the outer and inner circles are symbols representing the components that the makers of these symbols believed composed the world.

Chinese K’o-ssu depicting Mount Meru. This elaborate tapestry-woven mandala, or cosmic diagram, illustrates Indian imagery introduced into China in combination with the advent of Esoteric Buddhism. ( Public Domain )

A Map of this Cosmos and Soul

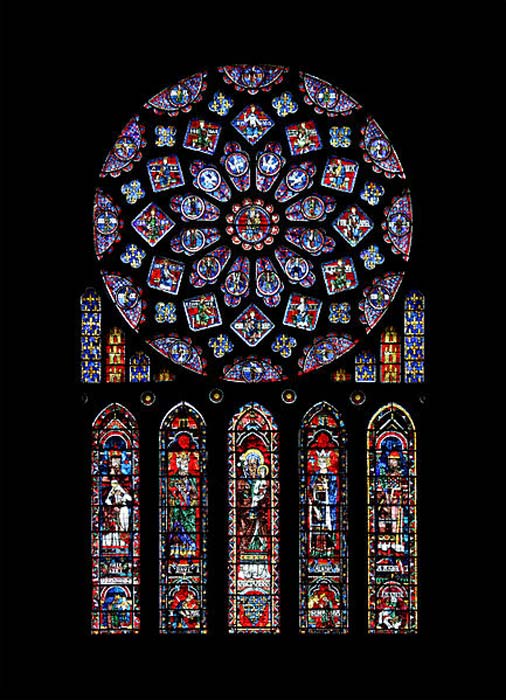

Although mandalas feature prominently in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and other Indian religions, symbols similar to the mandala may also be found in the Christian world. The dromenon is a diagram on the floor of the Chartres Cathedral in France which represents the soul traveling from the outer world to the sacred, inner world in which God resides.

Northern rose window of Chartres cathedral . ( Public Domain )

Although the mandala is a map of the cosmos, it may also be map of the soul; based on the belief in several traditions that the inner life of the spirit mirrors the outer life of the cosmos. This is seen in the earlier example of the Buddhist mandala. The outer border of the mandala typically reflects the beginnings of a person’s spiritual journey. The centre of the mandala represents the core of reality where a individual’s spiritual journey culminates. In Buddhism, it culminates in nirvana and the realm of enlightened ones beyond the temporary universe or samsara. In Christianity, the center of the mandala would be the location where God resides and where the traveller finds God and finds the real meaning of life and becomes exactly what he or she was meant to become.

In addition to its spiritual meanings, contemporary historians and anthropologists have also employed the expression “mandala” to characterize the nature of political institutions in Southeast Asia. European scholars studying the region noticed that statecraft in ancient Southeast Asia differed greatly from the Western or Chinese conception of the state. Rather than centralized states with defined boundaries and an established bureaucracy, polities of Southeast Asia consisted of a system of tributary states and satellite kingdoms that were internally autonomous however needed to pay tribute to a central power.

In this way, empires in Southeast Asia were considerably less centralized and characterized more by a powerful center than simply by their borders. Mandala has been picked as a word to refer to such empires to avoid using the term “state.” This is likely because these empires dominated through economic rather than territorial dominance, creating a political pattern which resembled a mandala, smaller and less significant polities at the far edge and the most powerful polities which characterized the political climate at the center.

The Bunga Mas (translates as Golden Flowers) was a tribute delivered every 3 years to the Siamese authorities in Bangkok, as a sign of friendship from the Malay rulers of the northern countries of the Peninsula (Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu and Patani). ( Public Domain )

The mandala has many different meanings, but it essentially represents a metaphysical map of the world. It reveals how a particular faith or civilization sees the relationship between the physical world, the spiritual world, and the divine. This contributes to an interesting question, what is the kind of a mandala depicting the metaphysical perspectives of the contemporary West? Knowing the way to assemble such a mandala would likely help us comprehend the West better and lead to a better comprehension of the mandala itself.

References

“Buddhist Art and Architecture: Symbolism of the Mandala.” Buddhanet. Available at: http://www.buddhanet.net/mandalas.htm

Cush, Denise, Catherine Robinson, and Michael York, eds.

.

Be the first to post a message!