Brain stimulation holds promise for anorexia

Brain stimulation holds promise for anorexia

Anorexia nervosa is a devastating, often fatal disease, in which voluntary food restriction severely compromises physical and mental health. Because current treatments, such as psychotherapy, are only minimally effective, many disease victims fight a lifelong battle and most will never recover. However, recent research into the neural underpinnings of anorexia provides hope that relief may be possible by regulating aberrant neural circuitry. A new study published in PLOS One by Jessica McClelland and colleagues from King’s College London offers preliminary support for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) as a viable therapy for anorexia.

Hitting reset to dysfunctional brain circuits

Anorexia is characterized by maladaptive behavior, such as abnormal cognitive flexibility, emotional regulation, and habit learning, which has been linked to dysfunction in frontal, limbic and striatal brain networks. The prefrontal cortex in particular is thought to be a critical hub in this aberrant network, as its hypoactivity may lead to poor impulse control underlying many of the symptoms of eating disorders. Restoring function to the prefrontal cortex therefore holds promise for resetting dysfunctional neural circuits and ultimately ameliorating disease symptoms. Modulating neural function noninvasively can be achieved with brain stimulation techniques such as rTMS, which, by applying repeated magnetic pulses over the scalp, induces an electric current in nearby neurons and alters cortical excitability. RTMS to the prefrontal cortex is FDA approved to treat depression, is effective at treating other psychiatric disorders including addiction and schizophrenia, and has shown early but inconsistent efficacy for alleviating symptoms of eating disorders.

To determine whether rTMS may be similarly beneficial for normalizing brain function in anorexia, the researchers tested 49 women with either restrictive or binge/purge subtypes of anorexia. Twenty-one of the women underwent real rTMS, while 28 underwent sham rTMS, to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Before and after treatment both groups completed a food challenge test to assess their response to enticing foods and gauge their symptoms. They also performed a temporal discounting task, which measures impulsivity and may therefore be sensitive to the altered inhibitory control that occurs in eating disorders.

A hint of therapeutic promise

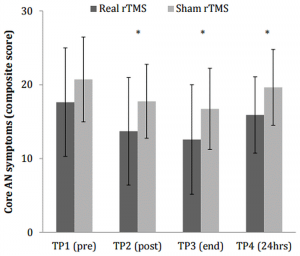

The researchers were mainly interested in whether rTMS could attenuate “core” symptoms of anorexia, such as urges to restrict eating, or feelings of fullness and fatness. Core symptoms were reduced after both real and sham treatments, suggesting at least some degree of a placebo effect. However, there was a trend for stronger symptom attenuation at multiple time-points – up to a day after treatment – for those who experienced real compared to sham rTMS. A closer look revealed a trend for lower reports of feeling fat after real rTMS compared to sham. Furthermore, the real treatment was also associated with less impulsivity (as assessed with the temporal discounting task) after rTMS, an effect that was only significant for the restrictive subtype of anorexia.

The path to the clinic

Based on these findings, should practitioners begin prescribing brain stimulation to eating disorder patients? Well, not quite yet. While the study’s results are encouraging, their effects were not overwhelmingly strong, and the authors acknowledge their study was possibly underpowered. Before rTMS translates to the clinic, its therapeutic potential needs to be further evaluated and the target patient population and optimal protocol should be better characterized. Even if these results hold up, it’s still not clear whether the benefits of rTMS are specific to anorexia, perhaps by resetting underactive neural function to normal levels, or whether rTMS similarly modulates healthy brain activity and behaviors. For example, would altered impulsivity and emotional responses to food also occur in healthy individuals after rTMS? McClelland admits that “Including healthy controls in this study would have been useful as a comparison group, to see if the rTMS in people with anorexia encourages more ‘normal’ responses,” and her group plans to include a healthy comparison group in future studies.

Furthermore, other brain stimulation tools may be equally or more effective, so comparative studies are needed to determine the ideal therapeutic technique. McClelland explains that

“We selected rTMS because there is more literature on its use and efficacy in other neuro-circuit based psychiatric disorders. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a slightly newer technique and hasn’t yet been investigated in eating disorders as widely as rTMS. This doesn’t mean that tDCS may not be as, if not more, effective than rTMS.”

And because the neural mechanisms of eating disorder subtypes presumably differ, the efficacy of rTMS may depend on the patient’s particular set of disease symptoms and illness duration. Targeting therapies at the individual patient level could be an ideal treatment approach, but will require further research to determine what stimulation protocols are optimal for particular symptom profiles.

According to McClelland, “Our single-session study was experimental and therefore only looked at the short-term, transient effects of rTMS in people with anorexia. We wouldn’t expect a single-session of rTMS to have long lasting therapeutic effects.” Therefore, in a critical step along the path to the clinic, McClelland and colleagues are currently doing a randomized clinical trial of 20 sessions of either real or placebo rTMS in individuals with anorexia.

Although preliminary, this study offers early hope for the millions of Americans presently suffering from anorexia. Effective relief from an otherwise debilitating, unrelenting disease may be just around the corner.

by PLOS

Be the first to post a message!