At a Time of Zealotry, Spinoza Matters More than Ever

At a Time of Zealotry, Spinoza Matters More than Ever

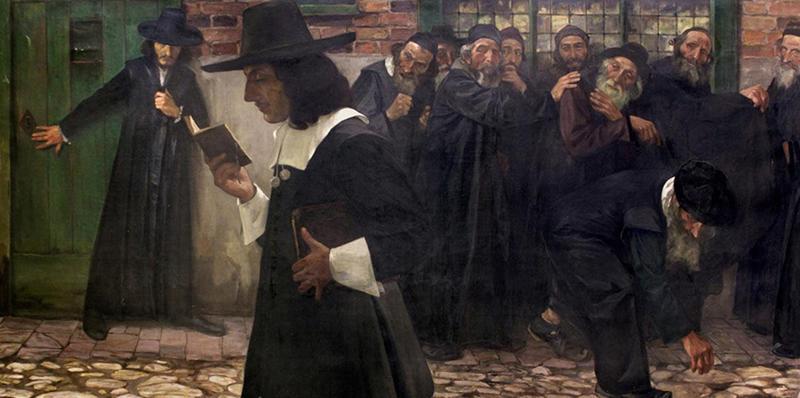

In July 1656, the 23-year-old Bento de Spinoza was excommunicated from the Portuguese-Jewish congregation of Amsterdam. It was the harshest punishment of herem (ban) ever issued by that community. The extant document, a lengthy and vitriolic diatribe, refers to the young man’s ‘abominable heresies’ and ‘monstrous deeds’. The leaders of the community, having consulted with the rabbis and using Spinoza’s Hebrew name, proclaim that they hereby ‘expel, excommunicate, curse, and damn Baruch de Spinoza’. He is to be ‘cast out from all the tribes of Israel’ and his name is to be ‘blotted out from under heaven’.

Over the centuries, there have been periodic calls for the herem against Spinoza to be lifted. Even David Ben-Gurion, when he was prime minister of Israel, issued a public plea for ‘amending the injustice’ done to Spinoza by the Amsterdam Portuguese community. It was not until early 2012, however, that the Amsterdam congregation, at the insistence of one of its members, formally took up the question of whether it was time to rehabilitate Spinoza and welcome him back into the congregation that had expelled him with such prejudice. There was, though, one thing that they needed to know: should we still regard Spinoza as a heretic?

Unfortunately, the herem document fails to mention specifically what Spinoza’s offences were – at the time he had not yet written anything – and so there is a mystery surrounding this seminal event in the future philosopher’s life. And yet, for anyone who is familiar with Spinoza’s mature philosophical ideas, which he began putting in writing a few years after the excommunication, there really is no such mystery. By the standards of early modern rabbinic Judaism – and especially among the Sephardic Jews of Amsterdam, many of whom were descendants of converso refugees from the Iberian Inquisitions and who were still struggling to build a proper Jewish community on the banks of the Amstel River – Spinoza was a heretic, and a dangerous one at that.

What is remarkable is how popular this heretic remains nearly three and a half centuries after his death, and not just among scholars. Spinoza’s contemporaries, René Descartes and Gottfried Leibniz, made enormously important and influential contributions to the rise of modern philosophy and science, but you won’t find many committed Cartesians or Leibnizians around today. The Spinozists, however, walk among us. They are non-academic devotees who form Spinoza societies and study groups, who gather to read him in public libraries and in synagogues and Jewish community centres. Hundreds of people, of various political and religious persuasions, will turn out for a day of lectures on Spinoza, whether or not they have ever read him. There have been novels, poems, sculptures, paintings, even plays and operas devoted to Spinoza. This is all a very good thing.

It is also a very curious thing. Why should a 17th-century Portuguese-Jewish philosopher whose dense and opaque writings are notoriously difficult to understand incite such passionate devotion, even obsession, among a lay audience in the 21st century? Part of the answer is the drama and mystery at the centre of his life: why exactly was Spinoza so harshly punished by the community that raised and nurtured him? Just as significant, I suspect, is that everyone loves an iconoclast – especially a radical and fearless one that suffered persecution in his lifetime for ideas and values that are still so important to us today. Spinoza is a model of intellectual courage. Like a prophet, he took on the powers-that-be with an unflinching honesty that revealed ugly truths about his fellow citizens and their society.

Spinoza is a role model for intellectual opposition to those who try to get citizens to act contrary to their own best interests

Much of Spinoza’s philosophy was composed in response to the precarious political situation of the Dutch Republic in the mid-17th century. In the late 1660s, the period of ‘True Freedom’ – with the liberal and laissez-faire regents dominating city and provincial governments – was under threat by the conservative ‘Orangist’ faction (so-called because its partisans favoured a return of centralised power to the Prince of Orange) and its ecclesiastic allies. Spinoza was afraid that the principles of toleration and secularity enshrined in the founding compact of the United Provinces of the Netherlands were being eroded in the name of religious conformity and political and social orthodoxy. In 1668, his friend and fellow radical Adriaan Koerbagh was convicted of blasphemy and subversion. He died in his cell the next year. In response, Spinoza composed his ‘scandalous’ Theological-Political Treatise, published to great alarm in 1670.

Spinoza’s views on God, religion and society have lost none of their relevance. At a time when Americans seem willing to bargain away their freedoms for security, when politicians talk of banning people of a certain faith from our shores, and when religious zealotry exercises greater influence on matters of law and public policy, Spinoza’s philosophy – especially his defence of democracy, liberty, secularity and toleration – has never been more timely. In his distress over the deteriorating political situation in the Dutch Republic, and despite the personal danger he faced, Spinoza did not hesitate to boldly defend the radical Enlightenment values that he, along with many of his compatriots, held dear. In Spinoza we can find inspiration for resistance to oppressive authority and a role model for intellectual opposition to those who, through the encouragement of irrational beliefs and the maintenance of ignorance, try to get citizens to act contrary to their own best interests.

Spinoza’s philosophy is founded upon a rejection of the God that informs the Abrahamic religions. His God lacks all the psychological and moral characteristics of a transcendent, providential deity. The Deus of Spinoza’s philosophical masterpiece, the Ethics (1677), is not a kind of person. It has no beliefs, hopes, desires or emotions. Nor is Spinoza’s God a good, wise and just lawgiver who will reward those who obey its commands and punish those who go astray. For Spinoza, God is Nature, and all there is is Nature (his phrase is Deus sive Natura, ‘God or Nature’). Whatever is exists in Nature, and happens with a necessity imposed by the laws of Nature. There is nothing beyond Nature and there are no departures from Nature’s order – miracles and the supernatural are an impossibility.

There are no values in Nature. Nothing is intrinsically good or bad, nor does Nature or anything in Nature exist for the sake of some purpose. Whatever is, just is. Early in the Ethics, Spinoza says that ‘all the prejudices I here undertake to expose depend on this one: that men commonly suppose that all natural things act, as men do, on account of an end; indeed, they maintain as certain that God himself directs all things to some certain end; for they say that God has made all things for man, and man that he might worship God’.

Spinoza is often labelled a ‘pantheist’, but ‘atheist’ is a more appropriate term. Spinoza does not divinise Nature. Nature is not the object of worshipful awe or religious reverence. ‘The wise man,’ he says, ‘seeks to understand Nature, not gape at it like a fool’. The only appropriate attitude to take toward God or Nature is a desire to know it through the intellect.

People who are led by passion rather than reason are easily manipulated

The elimination of a providential God helps to cast doubt on what Spinoza regards as one of the most pernicious doctrines promoted by organised religions: the immortality of the soul and the divine judgment it will undergo in some world-to-come. If a person believes that God will reward the virtuous and punish the vicious, one’s life will be governed by the emotions of hope and fear: hope that one is among the elect, fear that one is destined for eternal damnation. A life dominated by such irrational passions is, in Spinoza’s terms, a life of ‘bondage’ rather than a life of rational freedom.

People who are led by passion rather than reason are easily manipulated by ecclesiastics. This is what so worried Spinoza in the late 1660s, as the more repressive and intolerant elements in the Reformed Church gained influence in Holland. It remains no less a threat to enlightened, secular democracy today, as religious sectarians exercise a dangerous influence on public life.

In order to undermine such religious meddling in civic affairs and personal morality, Spinoza attacked the belief in the afterlife of an immortal soul. For Spinoza, when you’re dead, you’re dead. There might be a part of the human mind that is ‘eternal’. The truths of metaphysics, mathematics, etc, that one acquires during this lifetime and that might now belong to one’s mind will certainly remain once one has passed away – they are, after all, eternal truths – but there is nothing personal about them. The rewards or benefits such knowledge brings are for this world, not some alleged world-to-come.

The more one knows about Nature, and especially about oneself as a human being, the more one is able to avoid the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, to navigate the obstacles to happiness and wellbeing that a person living in Nature necessarily faces. The result of such wisdom is peace of mind: one is less subject to the emotional extremes that ordinarily accompany the gains and losses that life inevitably brings, and one no longer dwells anxiously on what is to come after death. As Spinoza eloquently puts it, ‘the free man thinks of death least of all things, and his wisdom is a meditation on life, not on death’.

Clergy seeking to control the lives of citizens have another weapon in their arsenal. They proclaim that there is one and only one book that will reveal the word of God and the path toward salvation and that they alone are its authorised interpreters. In fact, Spinoza claims, ‘they ascribe to the Holy Spirit whatever their wild fancies have invented’.

One of Spinoza’s more famous, influential and incendiary doctrines concerns the origin and status of Scripture. The Bible, Spinoza argues in the Theological-Political Treatise, was not literally authored by God. God or Nature is metaphysically incapable of proclaiming or dictating, much less writing, anything. Scripture is not ‘a message for mankind sent down by God from heaven’. Rather, it is a very mundane document. Texts from a number of authors of various socio-economic backgrounds, writing at different points over a long stretch of time and in differing historical and political circumstances, were passed down through generations in copies after copies after copies.

Finally, a selection of these writings was put together (with some arbitrariness, Spinoza insists) in the Second Temple period, most likely under the editorship of Ezra, who was only partially able to synthesise his sources and create a single work from them. This imperfectly composed collection was itself subject to the changes that creep into a text during a transmission process of many centuries. The Bible as we have it is simply a work of human literature, and a rather ‘faulty, mutilated, adulterated, and inconsistent’ one at that. It is a mixed-breed by its birth and corrupted by its descent and preservation, a jumble of texts by different hands, from different periods and for different audiences.

Spinoza supplements his theory of the human origins of Scripture with an equally deflationary account of its authors. The prophets were not especially learned individuals. They did not enjoy a high level of education or intellectual sophistication. They certainly were not philosophers or physicists or astronomers. There are no truths about nature or the cosmos to be found in their writings (Joshua believed that the Sun revolved around the Earth). Neither are they a source of metaphysical or even theological truths. The prophets often had naïve, even philosophically false beliefs about God.

They were, however, morally superior individuals with vivid imaginations, and so there is a truth to be gleaned from all of Scripture, one that comes through loud and clear and in a non-mutilated form. The ultimate teaching of Scripture, whether the Hebrew Bible or the Christian Gospels, is in fact a rather simple one: practice justice and loving-kindness to your fellow human beings.

That basic moral message is the upshot of all the commandments and the lesson of all the stories of Scripture, surviving whole and unadulterated through all the differences of language and all the copies, alterations, corruptions and scribal errors that have crept into the text over the centuries. It is, Spinoza insists, there in the Hebrew prophets (‘Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against one of your people, but love your neighbour as yourself’ ). Spinoza writes: ‘I can say with certainty, that in the matter of moral doctrine I have never observed a fault or variant reading that could give rise to obscurity or doubt in such teaching.’ The moral doctrine is the clear and universal message of the Bible, at least for those who are not prevented from reading it properly by prejudice, superstition or a thirst for power.

Does Spinoza believe that there is any sense in which the Bible can be said to be ‘divine’? Certainly not in the sense central to fundamentalist, or even traditional, versions of the Abrahamic religions. For Spinoza, the divinity of Scripture – in fact, the divinity of any writing – is a purely functional property. A work of literature or art is ‘sacred’ or ‘divine’ only because it is effective at presenting the ‘word of God’.

If The Tempest moves one toward justice and mercy, or Hard Times toward love and charity, then these works too are divine and sacred

What is the ‘word of God’, the ‘universal divine law’? It is precisely the message that remains ‘unmutilated’ and ‘uncorrupted’ throughout the Biblical texts: love your neighbours and treat them with justice and charity. But Scripture, perhaps more than any other work of literature, excels at motivating people to follow that lesson and emulate its (fictional) portrayal of God’s justice and mercy in their lives. Spinoza notes that ‘a thing is called sacred and divine when its purpose is to foster piety and religion, and it is sacred only for as long as men use it in a religious way’. In other words, the divinity of Scripture lies in the fact that it is, above all else, an especially morally edifying work of literature.

And yet, for just this reason, Scripture will not be the only work of literature that is ‘divine’. If reading William Shakespeare’s The Tempest or Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn moves one toward justice and mercy, or if reading Charles Dickens’s Hard Times inspires one toward love and charity, then these works too are divine and sacred. The word of God, Spinoza says, is ‘not confined within the compass of a set number of books’.

In a letter to Spinoza, the Cartesian Lambert van Velthuysen objects that, according to the Theological-Political Treatise, ‘the Koran, too, is to be put on a level with the Word of God’, since ‘the Turks… in obedience to the command of their prophet, cultivate those moral virtues about which there is no disagreement among nations’. Spinoza acknowledges the implication, but does not see it as an objection. He is perfectly willing to allow that there are other true prophets besides those of Scripture and other sacred books outside the Jewish and Christian canons.

The Bible’s moral message and its prescriptions for how we are to treat other human beings represents the authentic ‘word of God’. Spinoza insists, then, that true piety or religion has nothing whatsoever to do with ceremonies or rituals. Dietary restrictions, liturgical and sacrificial practices, prayers – all such elements typical of organised religions are but superstitious behaviours that, whatever might have been their historico-political origins, are now devoid of any raison d’être. They continue to be promoted by clergy only to create docile and obedient worshippers.

What Spinoza regards as ‘true religion’ and ‘true piety’ requires no belief in any historical events, supernatural incidents or metaphysical doctrines, and it prescribes no devotional rites. It does not demand accepting any particular theology of God’s nature or philosophical claims about the cosmos and its origins. The divine law directs us only on how to behave with justice and charity toward other human beings. ‘ to uphold justice, help the helpless, do no murder, covet no man’s goods, and so on’. All the other rituals or ceremonies of the Bible’s commandments are empty practices that ‘do not contribute to blessedness and virtue’.

True religion is nothing more than moral behaviour. It is not what you believe, but what you do that matters. Writing to the Englishman and secretary to the Royal Society Henry Oldenburg in 1675, Spinoza says that ‘the chief distinction I make between religion and superstition is that the latter is founded on ignorance, the former on wisdom’.

The political ideal that Spinoza promotes in the Theological-Political Treatise is a secular, democratic commonwealth, one that is free from meddling by ecclesiastics. Spinoza is one of history’s most eloquent advocates for freedom and toleration. The ultimate goal of the Treatise is enshrined in both the book’s subtitle and in the argument of its final chapter: to show that ‘freedom to philosophise may not only be allowed without danger to piety and the stability of the republic, but that it cannot be refused without destroying the peace of the republic and piety itself’.

All opinions whatsoever, including religious opinions, are to be absolutely free and unimpeded, both by necessity and by right. ‘It is impossible for the mind to be completely under another’s control; for no one is able to transfer to another his natural right or faculty to reason freely and to form his own judgment on any matters whatsoever, nor can he be compelled to do so’. Indeed, any effort by a sovereign to rule over the beliefs and opinions of citizens can only backfire, as it will ultimately serve to undermine the sovereign’s own authority. In a passage that is both obviously right and extraordinarily bold for its time, Spinoza writes:

a government that attempts to control men’s minds is regarded as tyrannical, and a sovereign is thought to wrong his subjects and infringe their right when he seeks to prescribe for every man what he should accept as true and reject as false, and what are the beliefs that will inspire him with devotion to God. All these are matters belonging to individual right, which no man can surrender even if he should so wish.

A sovereign can certainly try to limit what people think, but the result of such a vain and foolhardy policy would be to create only resentment and opposition to its rule. Still, the toleration of beliefs is one thing. The more difficult case concerns the liberty of citizens to express those beliefs, either in speech or in writing. And here Spinoza goes further than anyone else in the 17th century:

Utter failure will attend any attempt in a commonwealth to force men to speak only as prescribed by the sovereign despite their different and opposing opinions … The most tyrannical government will be one where the individual is denied the freedom to express and to communicate to others what he thinks, and a moderate government is one where this freedom is granted to every man.

Spinoza’s argument for freedom of expression is based both on the right (or power) of citizens to speak as they desire, as well as on the fact that (as in the case of belief) it would be counter-productive for a sovereign to try to restrain that freedom. No matter what laws are enacted against speech and other means of expression, citizens will continue to say what they believe, only now they will do so in secret. Any attempt to suppress freedom of expression will, once again, only weaken the bonds of loyalty that unite subjects to sovereign. In Spinoza’s view, intolerant laws lead ultimately to anger, revenge and sedition.

The right of the sovereign should be restricted to men’s actions, with everyone being allowed to think what he will and to say what he thinks’

There is to be no criminalisation of ideas in the well-ordered state. The freedom of philosophising must be upheld for the sake of a healthy, secure and peaceful commonwealth, and material and intellectual progress. Spinoza understands that there will be some unpleasant consequences entailed by the broad respect for civil liberties. There will be public disputes, even factionalism, as citizens express their opposing views on political, social, moral and religious questions. However, this is what comes with a healthy, democratic and tolerant society.

‘The state can pursue no safer course than to regard piety and religion as consisting solely in the exercise of charity and just dealing, and that the right of the sovereign, both in religious and secular spheres, should be restricted to men’s actions, with everyone being allowed to think what he will and to say what he thinks’. This sentence, a wonderful statement of the modern principle of toleration, is perhaps the real lesson of the Treatise, and should be that for which Spinoza is best remembered.

When, in 2012, a member of the Portuguese-Jewish congregation in Amsterdam insisted that it was finally time for the community to consider revoking the herem on Spinoza, the ma’amad, or lay-leaders, of the community sought outside counsel for such a momentous decision. They convened a committee – myself, along with three other scholars – to answer various questions about the philosophical, historical, political, and religious circumstances of Spinoza’s ban. While they did not ask us to recommend any particular course of action, they did want our opinions on what might be the advantages and disadvantages to lifting the ban.

We submitted our reports, and more than a year passed without any news. Finally, in the summer of 2013, we received a letter informing us that the congregation’s rabbi had decided that the herem was not to be revoked. In his opinion, Spinoza was indeed a heretic. He added that while we can all appreciate freedom of expression in the civic domain, there is no reason to expect such freedom within the world of orthodox Judaism. Moreover, he asked rhetorically, are the leaders of the community today that much wiser and better informed about Spinoza’s case than the rabbis who punished him in the first place?

No doubt, Spinoza would have found the whole affair amusing. If asked whether he would like to be readmitted to ‘the people of Israel’, he would most likely have replied: ‘Do whatever you want. I couldn’t care less.’

Steven Nadler

/Aeon

Be the first to post a message!