Toxic Stress — What We Can Do to Protect Our Children from The Global Epidemic

Toxic Stress — What We Can Do to Protect Our Children from The Global Epidemic

The future of any society depends on its ability to foster the healthy development of the next generation. Extensive research on the biology of stress now shows that healthy development can be derailed by excessive or prolonged activation of stress response systems in the body and brain. Such toxic stress can have damaging effects on learning, behavior, and health across the lifespan.

Learning how to cope with adversity is an important part of healthy child development. When we are threatened, our bodies prepare us to respond by increasing our heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones, such as cortisol. When a young child’s stress response systems are activated within an environment of supportive relationships with adults, these physiological effects are buffered and brought back down to baseline. The result is the development of healthy stress response systems. However, if the stress response is extreme and long-lasting, and buffering relationships are unavailable to the child, the result can be damaged, weakened systems and brain architecture, with lifelong repercussions.

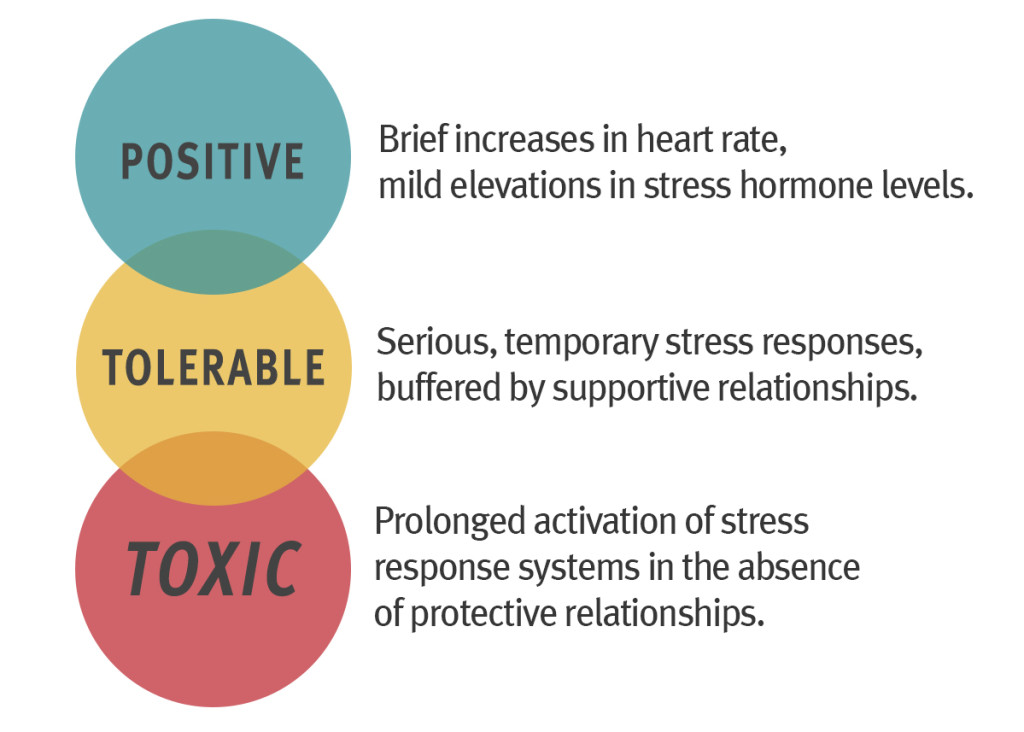

It’s important to distinguish among three kinds of responses to stress: positive, tolerable, and toxic. As described below, these three terms refer to the stress response systems’ effects on the body, not to the stressful event or experience itself:

Positive stress response is a normal and essential part of healthy development, characterized by brief increases in heart rate and mild elevations in hormone levels. Some situations that might trigger a positive stress response are the first day with a new caregiver or receiving an injected immunization.

Tolerable stress response activates the body’s alert systems to a greater degree as a result of more severe, longer-lasting difficulties, such as the loss of a loved one, a natural disaster, or a frightening injury. If the activation is time-limited and buffered by relationships with adults who help the child adapt, the brain and other organs recover from what might otherwise be damaging effects.

Toxic stress response can occur when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity—such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and/or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship—without adequate adult support. This kind of prolonged activation of the stress response systems can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems, and increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment, well into the adult years.

When toxic stress response occurs continually, or is triggered by multiple sources, it can have a cumulative toll on an individual’s physical and mental health—for a lifetime. The more adverse experiences in childhood, the greater the likelihood of developmental delays and later health problems, including heart disease, diabetes, substance abuse, and depression. Research also indicates that supportive, responsive relationships with caring adults as early in life as possible can prevent or reverse the damaging effects of toxic stress response.

Questions & Answers

Is all stress damaging?

No. The prolonged activation of the body’s stress response systems can be damaging, but some stress is a normal part of life. Learning how to cope with stress is an important part of development. We do not need to worry about positive stress, which is short-lived, or tolerable stress, which is more serious but is buffered by supportive relationships. However, the constant activation of the body’s stress response systems due to chronic or traumatic experiences in the absence of caring, stable relationships with adults, especially during sensitive periods of early development, can be toxic to brain architecture and other developing organ systems.

What Causes Stress to Become Toxic

The terms positive, tolerable, and toxic stress refer to the stress response systems’ effects on the body, not to the stressful event itself. Because of the complexity of stress response systems, the three levels are not clinically quantifiable—they are simply a way of categorizing the relative severity of responses to stressful conditions. The extent to which stressful events have lasting adverse effects is determined in part by the individual’s biological response (mediated by both genetic predispositions and the availability of supportive relationships that help moderate the stress response), and in part by the duration, intensity, timing, and context of the stressful experience.

What Can We DO to Prevent Damage from Toxic Stress Response?

The most effective prevention is to reduce exposure of young children to extremely stressful conditions, such as recurrent abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver mental illness or substance abuse, and/or violence or repeated conflict. Programs or services can remediate the conditions or provide stable, buffering relationships with adult caregivers. Research shows that, even under stressful conditions, supportive, responsive relationships with caring adults as early in life as possible can prevent or reverse the damaging effects of toxic stress response.

When should we worry about toxic stress?

If at least one parent or caregiver is consistently engaged in a caring, supportive relationship with a young child, most stress responses will be positive or tolerable. For example, there is no evidence that, in a secure and stable home, allowing an infant to cry for 20 to 30 minutes while learning to sleep through the night will elicit a toxic stress response. However, there is ample evidence that chaotic or unstable circumstances, such as placing children in a succession of foster homes or displacement due to economic instability or a natural disaster, can result in a sustained, extreme activation of the stress response system.

Stable, loving relationships can buffer against harmful effects by restoring stress response systems to “steady state.” When the stressors are severe and long-lasting and adult relationships are unresponsive or inconsistent, it’s important for families, friends, and communities to intervene with support, services, and programs that address the source of the stress and the lack of stabilizing relationships in order to protect the child from their damaging effects.

Additional Reading

The JPB Research Network on Toxic Stress, a project of the Center on the Developing Child, is committed to reducing the prevalence of lifelong health impairments caused by toxic stress in early childhood. Its work addresses the need to develop rigorous, versatile methods for identifying young children and adults who experience toxic stress.

Tackling Toxic Stress, a multi-part series of journalistic articles, examines how policymakers, researchers, and practitioners in the field are re-thinking services for children and families based on the science of early childhood development and an understanding of the consequences of adverse early experiences and toxic stress.

Be the first to post a message!