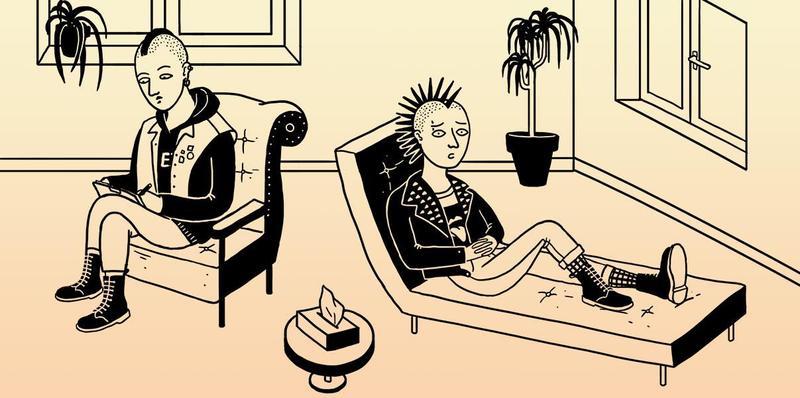

The Punk Counsellor Using his DIY Ethic to Promote Mental Health and Wellbeing

The Punk Counsellor Using his DIY Ethic to Promote Mental Health and Wellbeing

Peer counsellor and punk Craig Lewis suffered three decades of unnecessary medication and abuse at the hands of the psychiatric system. Today, he offers young punks struggling with mental health challenges an alternative path to recovery.

“I didn’t know who I was because I was drugged my whole life,” explains 43-year-old Boston punk rocker Craig Lewis. “Everyone who’s ever known me from age 14 until last year knew somebody who was on 40 different medications.”

Peer counsellor and punk Craig Lewis suffered three decades of unnecessary medication and abuse at the hands of the psychiatric system. Today, he offers young punks struggling with mental health challenges an alternative path to recovery.

“I didn’t know who I was because I was drugged my whole life,” explains 43-year-old Boston punk rocker Craig Lewis. “Everyone who’s ever known me from age 14 until last year knew somebody who was on 40 different medications.”

For the last fourteen months, Craig has been entirely free of all psychiatric medication. The long withdrawal process has been brutal and painful, but now Craig has opened a new chapter in his life – and is starting to learn who he is, without the pharmaceutical cocktail that he attributes years of destructive destructive behaviour to. He’s determined to take his years of suffering and use them to help young, marginalised people in his own community – the punk community. As a certified peer counsellor, he’s using the punk principles of acceptance, inclusiveness and DIY to offer young people struggling with their own mental challenges an alternative path to recovery.

Craig was first institutionalised in 1988, aged just 14. He later discovered that his initial diagnosis showed no signs of any serious disorder, but until he found support to break the cycle, his parents and clinicians kept him on a conveyor belt of medication, institutionalisation, abuse and disempowerment. He’s now drawn a line under three decades of unnecessary suffering inflicted by the psychiatric system – and is determined to help punk kids avoid the damaging path he was forced down.

“I’m in a position now where I can build and build while creating a life for myself and helping others,” Craig says. “I’m learning the hard way, but this is the knowledge I bring to workshops and the training I do. I still get to do things punk rock and DIY, have my ethics and do what’s right. So I work with people who can pay me well, and I work for free with people who can’t pay because that’s the way to do things. I’m coming from the street, where you do whatever you can to make a difference in the world, outside the system. Isn’t that what punk rock is all about?”

Craig owes his survival to punk. When nobody else cared, the punk community in his hometown of Boston, Massachusetts accepted him and gave him a much-needed sense of belonging. He remembers vividly the first time he ever met another punk – the day he was first placed in a mental institution, on April 13, 1988, aged 14.

“That was one of the most F-ed up days of my life: I was lost in a psychiatric hospital with no idea why I was there,” Craig remembers. “That first day in hospital, there was a punk rocker there and she was so nice to me. She was wearing all black, boots, chains and earrings and she gave me cassettes of Dead Kennedys, Black Flag and Circle Jerks for my Walkman. I knew right there and then that was music I identified with – their energy resonated powerfully with me. From that point on I connected with music in a different way.”

Craig went in and out of a series of hospitals over the next three and a half years. Based on documents he’s seen from that time, he’s now convinced his parents displayed Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy, the obsession with having a sick child. Unable to find support from the people who should have protected him, his parent and medical professionals, he found sanctuary in punk. As a member of punk bands Weapons Grade and Melee, publisher of fanzine Upheaval and a DIY promoter for 20 years, he became a big figure in the Boston scene. But looking back, he feels the community that supported him when he had nowhere else to turn also encouraged behaviour that was damaging to himself and those around him.

Craig explains:

“Without question, the punk scene was a community of people who fully accepted how messed up I was”

“I found solace, I found safety and community even when I was so far off the rails. I still had a place to go, I had a place to be. That connection, that common bond was awesome and to this day I find great value and meaning in it. But at the same time, it’s a very self-destructive community.

Many people are drawn to it because of the acceptance, the community and the safety it provides. But when you’re going through life struggles, the emotional challenges that affect all young people, if you’re surrounded by perhaps similarly dysfunctional people, a lot of things happen that can get you into trouble: restlessness, substance abuse and other dangerous choices.”

Today, Craig is pushing to promote an open and honest debate in the punk community around mental health – from an understanding and supportive, insider’s perspective on the scene. He holds talks on mental health with punk communities across the US and Europe and has written two books Better Days – A Mental Health Recovery Workbook and You’re Crazy, a compilation of 25 first-person accounts of people from the punk scene who live with mental health struggles, addiction and trauma.

He also works day-to-day with young people one-one-one as a certified peer specialist. He’s part of a movement of non-clinicians who are trained to tap into their lived experience to help people, which is growing across the English-speaking world and also in Europe, Singapore and Malaysia.

As he discovers more about his own treatment and the poor choices that were made for him, he’s increasingly passionate about helping young people avoid the questionable diagnoses, damaging labels and pharmaceutical cocktails handed down to young people once they become embroiled in the psychiatric system. Talking with counsellors like Craig, who understand the experiences of the young people they work with and the communities they come from can be far more effective.

“People connect because we’re stripping away the shame and stigma,” Craig explains. “Human beings make reasonable responses to the situations they experience. Psychiatry professionals are trained and paid based on subjective diagnoses. I speak out about that and believe we shouldn’t be making things worse by using such negative language.

With our backgrounds in punk, we don’t see colour, we don’t see class, we don’t see gender, we don’t give a fuck about social barriers. We connect through being genuine and meeting people with their language. We connect with people around commonality and honesty. Treating people as human beings is the first step to treatment – whatever happened to them doesn’t define them.”

Craig is, and always will be, punk. But he’s looking at the community with fresh eyes and a new sense of purpose, in the hope that he can help people avoid the decades of trauma he experienced. As we’re wrapping up our conversation, I ask him how he feels when he wakes up each morning, medication-free.

“I now wake up every day with gratitude for all I have, the desire to live out all I can be and to help people,” he says. “I forgive my family, I forgive every doctor, I forgive them all.” Then he pulls up the sleeve of his shirt, puts his elbow up to the webcam and reads the message tattooed on his arm: “I will not allow my suffering to be wasted”.

by Alex King/huck

Be the first to post a message!