Tastebuds Hacking — Surprisingly Easy Ways to Trick Our Tongue

Tastebuds Hacking — Surprisingly Easy Ways to Trick Our Tongue

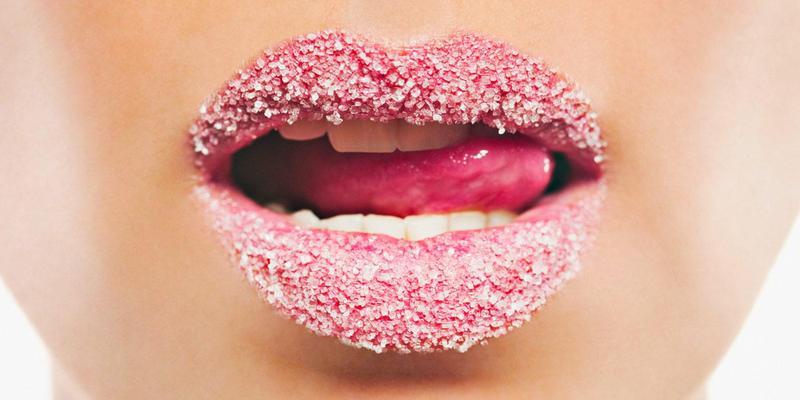

Why does toothpaste give orange juice a weird aftertaste? It’s one of many surprisingly easy ways to trick your tongue – and your brain – into experiencing strange flavours. What’s going on?

Your tongue is not a blank slate. What you’ve just eaten can change the flavour of what you eat next – for better or for worse. It’s all because your taste buds respond differently when the environment around them shifts – an effect you can use to go on a little mouth-hacking tour.

Let’s start with an artichoke. Eat one and then drink a glass of water and you might notice that the liquid tastes strangely sweet. Then there’s orange juice. Drink a glass after brushing your teeth with toothpaste, and the normally sweet drink tastes foul instead. And for mind-bending parlour tricks, nothing beats miracle fruit. These little red West African berries make anything sour taste sweet – and it’s a remarkably clean, pure sweetness.

To understand why these foods mess with your mind, first think about your tongue. It’s covered with little clusters of taste-sensitive cells, and each cell’s membrane is studded with proteins that function, essentially, as doorbells. When something – a molecule in food you’ve eaten – hits them just right, a message shoots from the cell to the brain, causing one of the five taste sensations: sweetness, bitterness, sourness, saltiness, or umami.

Stated that way, it sounds relatively simple, but researchers haven’t figured out all the details of taste yet: sweet, bitter, and umami have fairly clear relationships to specific cell proteins, but exactly how our tongues detect saltiness and sourness is still a bit of a mystery. And there’s a lot that goes on between your taste buds and your brain to create the sensation of taste that is still foggy.

But the basics are enough to help you understand, for instance, what is happening with the artichoke. The key is a substance in the vegetable called cynarin, according to Linda Bartoshuk, a taste scientist now at University of Florida, who authored a Science paper on the phenomenon in 1972. When you eat an artichoke, the cynarin quietly latches onto your sweet receptors without actually activating them. As you clear the table, wash the dishes, and move on to the next thing, the cynarin lurks on your tongue.

When you next drink a glass of water, however, the cynarin molecules are washed away, releasing the receptors. It’s this sudden release that triggers a message to the brain, generating the sensation of sweetness. And though it’s just a phantom taste, it feels just as distinct and real as a sensation from direct stimulation of the receptor by a sweet fruit.

Bartoshuk remembers her very first experiment into these lingering after-effects. She put various fluids on people’s tongues and then gave them water to see what happened: some of her subjects were certain the second fluid was flavoured with particular acids or sugars. “It was very funny, because all of the stimuli were water,” she says.

Curious orange

The culprit in the case of the toothpaste and orange juice is a detergent called sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS) that foams when you’re brushing your teeth. Detergent molecules like SLS have chemical properties that let them elbow their way into bubbles of fat molecules and disperse them. That’s all fine and good when you’re using dish soap to wipe spaghetti bolognese off the dinner plates. But the membranes of our biological cells are also made of fats. The current theory is that SLS somehow tampers with the membranes of the taste cells on our tongue. “It not only reduces your ability to taste sweet, it tends to add a bitter taste to acid,” says Bartoshuk. So when you drink orange juice under the influence of SLS, you taste none of its sweetness and its tartness comes across as bitter.

There’s a more direct way to briefly knock out your sweet taste, says Bartoshuk: just suck on a pill containing the Indian herb Gymnema sylvestre – sometimes known as the sugar destroyer. It knocks out your sweet receptors for about half an hour, meaning the tastes normally masked by sweetness jump out at you.

Recently, after eating a camembert-style cheese, I found an apple tasted awful, kind of soapy and bitter. Could something in the cheese have disabled my sweet receptors? Bartoshuk suggested an experiment – try the apple after some Gymnema and see if it has the same effect as the cheese.

And what of the miracle fruit? The substance behind its weird effects is called miraculin, and you can buy tablets that contain it online. The current thought is that miraculin attaches itself to your tongue, lurking like the cynarin. The hitchhiker is imperceptible until something acidic enters the mouth, whether that’s a slice of lime (my favourite – I can easily eat dozens of them under the influence) or salt-and-vinegar crisps.

The pH drop caused by the acid changes something – either the shape of the miraculin, so that it activates the sweet receptors, or the shape of the receptors, so that the miraculin can activate them – and instead of sourness you taste sweetness. Bartoshuk says that the tongue still registers the sour taste in food even under the influence of miracle fruit, but the signal is drowned out by the strength of the sweet avalanche.

All of this can make for a novel form of entertainment this holiday season. Several Christmases ago, my husband and I gave the family miracle fruit tablets as a gift. On Christmas afternoon we made a last-minute foray to the only store open that day and bought about 10lb of lemons, limes, and grapefruit. That evening, the festive dessert was citrus. It was lighter than pies or pudding, and beautiful and strange to boot.

By Veronique Greenwood/BBC

Be the first to post a message!