On Thomas Kuhn

On Thomas Kuhn

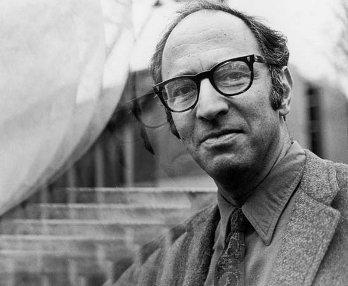

Thomas Kuhn, the notable physicist, logician, and student of the history of science, was brought into the world in 1922. He proceeded to turn into a significant and expansive running mastermind, and quite possibly the most powerful scholars of the twentieth century.

Kuhn’s 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, changed the way of thinking of science and changed the manner in which numerous researchers consider their work. Be that as it may, his impact expanded well past the foundation: The book was generally perused — and saturated mainstream society. One proportion of his impact is the boundless utilization of the expression “outlook change,” which he presented in articulating his perspectives about how science changes after some time.

Propelled, to a limited extent, by the hypotheses of analyst Jean Piaget, who considered youngsters’ to be as a progression of discrete stages set apart by times of change, Kuhn placed two sorts of logical change: steady advancements throughout what he called “typical science,” and logical insurgencies that intersperse these more steady periods. He proposed that logical unrest is not a matter of gradual development; they include “perspective changes.”

Discuss standards and perspective changes has since gotten ordinary — in science, yet additionally in business, social developments and the past. In a segment at The Globe and Mail, Robert Fulford portrays worldview as “a hybrid hit: It moved agilely from science to culture to sports to business.”

However, what, precisely, is a change in outlook? Or on the other hand, besides, a worldview?

The Merriam-Webster word reference offers the accompanying:

Straightforward Definition of worldview:

a model or example for something that might be duplicated

a hypothesis or a gathering of thoughts regarding how something ought to be done, made or pondered

Likewise, a change in perspective is characterized as “a significant change that happens when the standard perspective about or accomplishing something is supplanted by another and distinctive way.”

Over 50 years after Kuhn’s renowned book, these definitions may appear to be instinctive as opposed to specialized. In any case, do they catch what Kuhn really had as a main priority in building up a record of logical change?

It turns out this inquiry is difficult to reply to — not on the grounds that worldview has a particularly specialized or dark definition, but since it has many. In a paper distributed in 1970, Margaret Masterson introduced a cautious pursuit of Kuhn’s 1962 book. She distinguished 21 unmistakable faculties in which Kuhn utilized the term worldview. (Believe it or not: 21.)

Think about a couple of models.

Initially, a worldview could allude to an uncommon sort of accomplishment. Masterson cites Kuhn, who presents a worldview as reading material or exemplary model that is “adequately uncommon to draw in a suffering gathering of followers from contending methods of logical action,” however that is all the while “adequately open-finished to leave a wide range of issues for the reclassified gathering of experts to determine.” Writes Kuhn: “Accomplishments that share these two attributes I will consequently allude to as ‘standards.’ “

In any case, in different pieces of the content, standards cover more ground. Ideal models can offer general epistemological perspectives, similar to the “philosophical worldview started by Descartes,” or characterize a wide breadth of the real world, as when “Standards decide enormous territories of involvement with a similar time.”

Given this abundance of related uses, Masterson poses a provocative inquiry:

Is there, logically talking, anything distinct or general about the idea of a worldview which Kuhn is attempting to clarify? Or then again would he say he is only an antiquarian writer portraying various happenings which have happened throughout the historical backdrop of science, and alluding to them all by utilizing a similar word “worldview”?

Eventually, Masterson distills Kuhn’s 21 feelings of worldview into a more decent three, and she distinguishes what she sees as both novel and significant parts of Kuhn’s “worldview see” of science. However, for our motivations, Masterson’s examination reveals insight into two inquiries that end up being connected: what Kuhn implied by a worldview in any case, and how a solitary word figured out how to accept a particularly wide and far-reaching set of implications subsequent to being released by Kuhn’s book.

Obviously, Kuhn can’t be accused without any help for the way worldview — and its shiftier cousin — have proliferated in mainstream society. What he did was give some exemplary instances of the term that were adequately exceptional to pull in followers from more commonplace other options, yet adequately open-finished to leave a wide range of opportunities for others to investigate. Furthermore, that, I assume, is an accomplishment.