How a group of California nuns challenged the Catholic Church

How a group of California nuns challenged the Catholic Church

California in the 1960s was the epicenter for religious experimentation. Indian gurus and New Age prophets, Jesus freaks and Scientologists all found followings in the Golden State.

But among those searching for personal and social transformation, the unlikeliest seekers might have been a small community of Roman Catholic religious: the Immaculate Heart Sisters.

The Daughters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary was founded in Spain in 1848. Twenty-three years later, at the invitation of the bishop of California, 10 sisters came to the United States.

Initially, the nuns worked with the poor, but pivoted later to education. In 1886 they started teaching in Los Angeles. Over the next several years, they staffed Catholic schools, started a convent, and founded a high school and a school. The faculty, however, closed in 1981 because of financial problems. Among the high school’s most famous graduates is Meghan Markle, the fiancee of Prince Harry.

In 1924, the order separated from Spain. The women renamed themselves the California Institute of the Sisters of the Most Holy and Immaculate Heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The “new” order flourished: By the 1960s, it had 600 members, most of whom were teachers. And by 1967 almost 200 sisters worked in Los Angeles’ Catholic schools.

Led by broad-minded mother superiors, their order and their college were intellectually rigorous and open to diverse perspectives. They welcomed female speakers such as social activist Dorothy Day to campus as well as Protestant, Jewish and even Hindu religious leaders.

Meanwhile, change was stirring at the Vatican, the center of world Catholicism. In 1959, Pope John XXIII had invited Roman Catholic leaders to discuss the role of the Church in the modern world. From 1962 to 1965, this Second Vatican Council debated Catholicism’s future. Centuries had passed with little change in Church teaching, ritual, community life and worldview. But now the council would, in the words of the pope, “open the windows and let in the fresh air.”

Catholic leaders reviewed everything from interreligious dialogue to the role of the Church in the modern world. They even updated the traditional liturgy. The language changed from Latin to the vernacular, priests faced the people and popular music was welcomed into Mass.

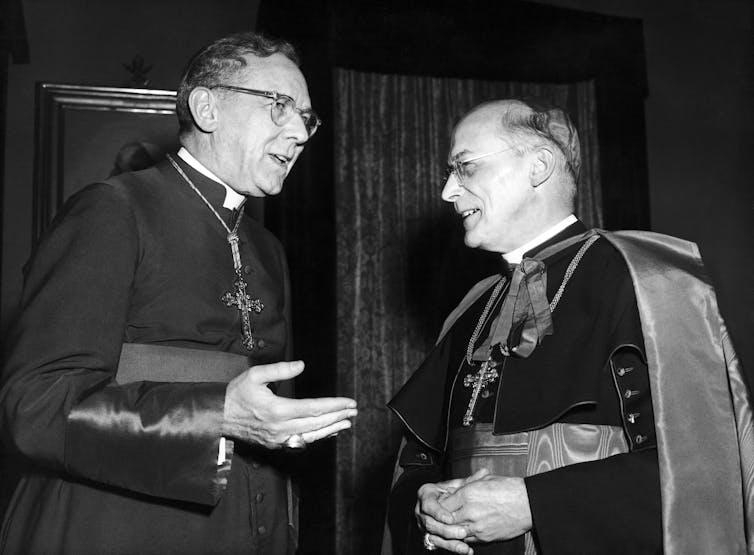

The debate over Vatican II’s achievements continues today. At the time, many Catholics were excited by the innovations, but others preferred the Church as it was. They were not eager to see the council’s intentions put into practice.” Among these conservatives was James Francis Cardinal McIntyre of Los Angeles.

James Francis Cardinal Mcintyre, Archbishop of Los Angeles, U.S., left. Source: AP Photo/Mario Torrisi

Challenging the Church hierarchy

Following the recommendations of the Second Vatican Council, the Immaculate Heart Sisters decided to review and renew their religious life. In 1963, the sisters began a multi-year study of their spiritual practice, community structure and mission. They met regularly to talk and pray about the future of their order.

According to Anita Caspary, the order’s head at the time, the nuns were inspired by the Second Vatican Council; the spirit of the times (that is, the 1960s); and the growth of diverse populations that were roiling Southern California.

Sister Anita Caspary. AP Photo/David S. Smith

She later wrote that in this “historic moment of faith and freedom,” the community saw itself as “part of the women’s struggle for equal status in the mid-20th century.”

Many of the council’s directives did indeed reflect cultural shifts, such as reaching out to the modern, secular world, that had inspired the sisters. But the women also were inspired by trends closer to home. For example, Caspary and her community were intrigued by humanistic psychology, the psychological school that emphasized personal growth and fulfillment and which had a significant West Coast following.

Until the 1960s, the women had followed Church rules that governed their religious as well as personal lives. Now, rather than assume that they all needed to pray, study or meditate in the same way or at the same time, they encouraged individual experimentation. When they did worship together, they wanted the freedom to decide when, where and how to do so.

Likewise, the sisters sought relief from Church mandates that controlled their daily activities, ranging from what they wore and what time they went to bed to which books they were allowed to read.

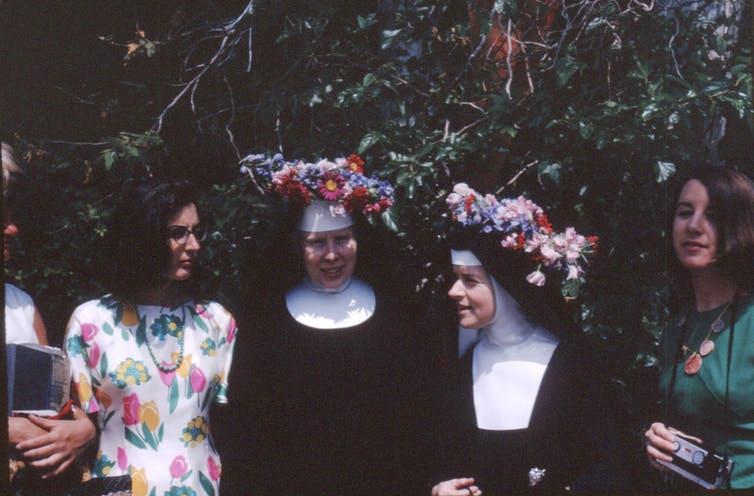

Sisters of the Immaculate Heart College preparing for a spring festival. Image courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles.

On October 14, 1967, the sisters celebrated what they called Promulgation Day, the announcement of plans for their order’s renewal. A new vision for their lives and their work, the document, for example, said that sisters who taught in religious schools would be allowed to pursue teaching credentials and graduate degrees to professionalize their work. Those who did not feel the call to teach could find other careers.

Additionally, each sister could choose the length, time and type of her individual prayer, and group prayer would be shaped by the community. They no longer had to seek permission from the mother superior for the small decisions of daily life. They would be free to set their bedtimes, see a doctor or make a quick trip to the store.

Opposition to the sisters

Two days later, on Oct. 16, a delegation of six sisters sat in the office of Los Angeles’ Cardinal McIntyre. Furious with the sisters’ plans for renewal, he first asked concerning their apparel: Did they really mean to wear street clothing to their classrooms? Caspary said they might, and an upset McIntyre ended the meeting.

Even when the cardinal’s men persuaded him to keep the dialogue, he refused to accept the order’s plan for renewal. Instead, he berated their defiance and doubted their devotion to spiritual life. As of June 1968, he advised them they would no longer teach in the city’s Catholic schools.

Over the subsequent six months, both the sisters and the cardinal presented formal cases to emissaries from the Vatican. Each side also sought aid from Church colleagues and from the court of public opinion. Unfortunately, several papers played up the battle as though the whole fight hinged on whether the sisters wore their traditional habits or street clothing.

By spring, the message was obvious: The Vatican would support the cardinal. According to official pronouncements, the women’s experimentation went too far. They hadn’t, in other words, worked within the guidelines of the male hierarchy.

Rather than give up their vision for spiritual renewal, nevertheless, 350 of this order’s 400 sisters started planning a new lay community outside the Church.

By the beginning of 1970, a lot of the Immaculate Heart sisters had decided to renounce their vows and reorganize as a lay community. The brand new group, the Immaculate Heart Community, was open to laypeople and clergy, men as well as women.

In the intervening years, the majority of the innovations the sisters sought – such as professionalizing standards, experimentation with community worship and giving sisters control of their everyday activities – were embraced by Catholics across the country.

The Immaculate Heart Sisters drew on their time and place to make a new vision of religious community. Their sources ranged from the reforms of the Second Vatican Council to the writings of California’s humanist psychologists. They also included women’s liberation, the anti-war movement along with the countercultural wave which rolled outside their convent door.

The California dream and its promise of new possibilities was fundamental to the religious journey of the Immaculate Heart Sisters. It continues to inspire new generations of seekers in and out of the Church.

Source: WTOP

Be the first to post a message!