The Alchemy and Artistry of Fayum Portrets

The Alchemy and Artistry of Fayum Portrets

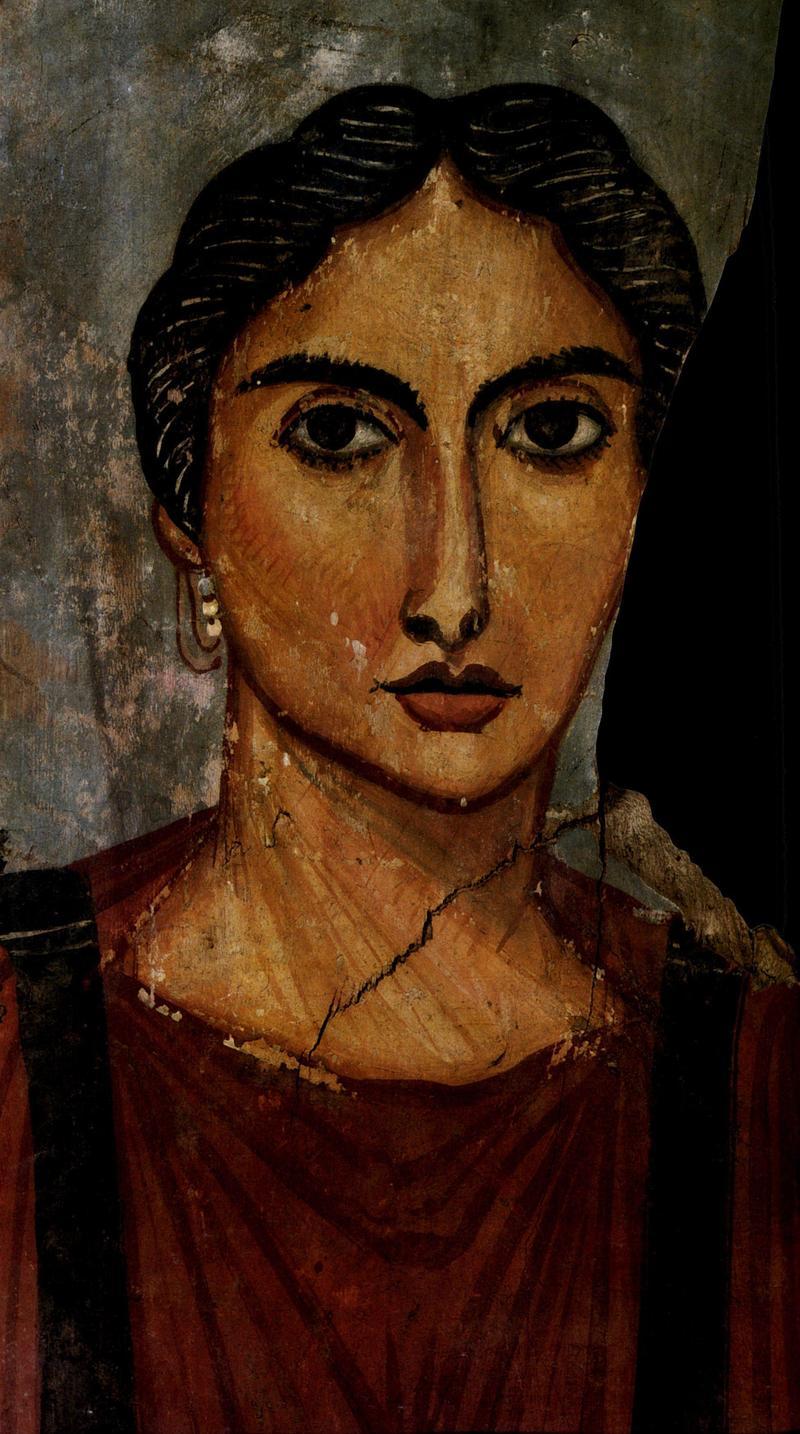

Her rapt, black eyes gaze out, as though she is waiting for one to ask her a question. Her necklace –a braid twirled and tucked in the crown of her head–hints in a noble position, as does her purple tunic, dangling earrings, and pile of necklaces dappled with pearls and gemstones. It’s been several millennia, therefore flecks of paint have sloughed off of the lifelike portrait, which has been fastened to her body during Egypt’s Coptic period, nearly 2,000 years ago.

Images such as this one, at the selection of the National Gallery of Art, are usually described as precursors to Western portraiture and also have captivated researchers for years. Known as Fayum paintings, for the Egyptian site where they have been excavated, they straddle both Greco-Roman and Egyptian styles. A thousand or so of those beguiling two-dimensional busts are currently in museums across the globe, where scientists have peppered them with queries and high tech imaging research.

To decode an early artist’s process or substances, researchers frequently analyze small samples they have scraped out of a painting, which may show, for example, the makeup of wax and paints and the sequence in which they had been applied. Researchers now frequently attempt using less-invasive, but still quite comprehensive, approaches. Last winter, for instance, a team in Northwestern enlisted a machine-learning algorithm to monitor brush strokes and establish the roots of different pigments on one of those paintings. Now, a group at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the National Gallery has employed a hybrid of three methods to find out more about this painting’s composition–and the civilization which produced it.

In a paper recently published in Nature Scientific Reports, the researchers explain how they used hyperspectral diffuse reflectance, luminescence, and X-ray fluorescence together, which enabled them to analyze everything from minerals in the pigments to underdrawing which was concealed in the finished edition. This approach also helped them connect artistic”production technology other ancient ‘industries’ and practices, such as mining, metallurgy, pottery, dyeing, pharmacopeia and alchemy,” Ioanna Kakoulli, a materials scientist at UCLA, and also one of the study’s lead authors, said in a statement.

“The decoration of garment is an excellent example of craftsmanship in real life being reflected within the painting,” said UCLA graduate student and coauthor Roxanne Radpour in a statement. The Stockholm Papyrus, an alchemy compendium composed in Greek in A.D. 300, holds more than 150 recipes, for example a handful for mixing up batches of madder dye, that was extracted from roots and utilized to imbue fabrics using a purple-red colour, such as the one visible on this particular figure’s dress. Just like it, in fact. Her posthumous portrait has been painted using the exact same assortment of pigment which coloured a garment she might have worn in life.

The lady’s individuality and life narrative have slipped into the sands of time, but it does not mean there still isn’t a lot to learn about her.

Be the first to post a message!