Taoism In Modern China

Taoism In Modern China

Last month, Shanghai’s City God Temple played host to a solemn congregation assembled in celebration of the birth of Laozi, an ancient philosopher broadly called the founder of Chinese Taoism. The service has been held on the 15th day of the next month in the Chinese lunar calendar, an auspicious day which Taoists consider to be the birthday of the Highest Lord Lao, one of Taoism’s three greatest gods.

Lord Lao is the deified form of the same Laozi who apparently wrote the Tao Te Ching, a classic work of Chinese philosophy written around the sixth century B.C.. During the Eastern Han Dynasty, Lord Lao allegedly reappeared before the Taoist celestial master Zhang Daoling, bestowing upon him the teachings which afterwards came to shape the orthodox beliefs of the Zhengyi sect, one of the significant Taoist denominations in China now.

For followers of Taoism, the Highest Lord Lao is the embodiment of the Tao, or”Way,” and the Tao Te Ching is among the most important Taoist scriptures. During the Tang Dynasty, the emperor gave Laozi the venerable title of”Highest Emperor of Mysterious Origin,” and from 840 A.D. onward, his birthday was rigorously observed by the royal court, when the nation’s larger Taoist temples held burial ceremonies for followers to fast and preach scripture. Lord Lao’s birthday is, in nature, as close as Taoism gets to Christmas in the West. Nevertheless regardless of the current resurgence of religion in China, Lord Lao had not enjoyed a birthday celebration on this scale for quite a while.

Last month’s celebrations in Shanghai were so important for two reasons. For starters, it had been the first time in many years the City God Temple hosted a large scale Taoist festival. Although Taoism is China’s only indigenous religion, its sway now pales compared with its previous status. A lot of people know the City God Temple as a tourist milestone and business center, but few understand it as a significant Taoist religious site.

Secondly, the ceremony itself revealed Taoism is adapting its image to attract new converts. Within the course of the afternoon , organizers deftly mixed tradition, commerce, and technologies to create a welcoming atmosphere for new and lapsed Taoists alike.

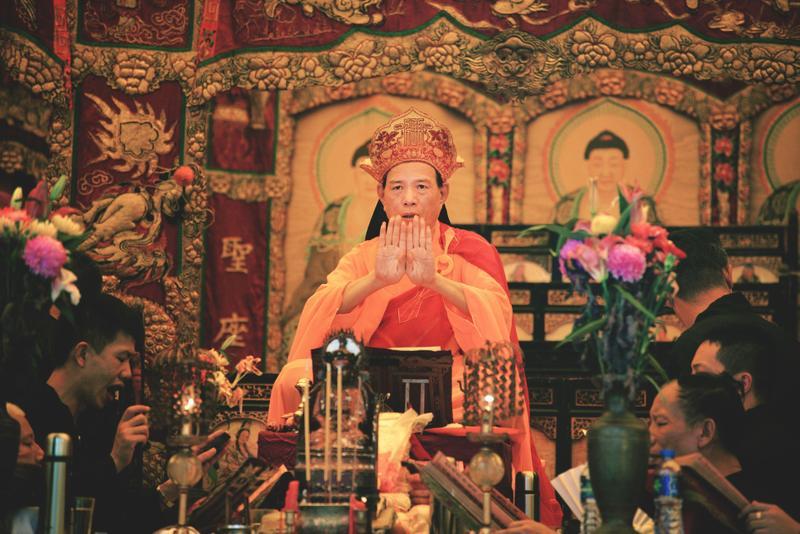

During morning , the temple abbot started with a ritual preaching of the Tao. Afterwards, he conducted the tradition of natural audiences with Laozi, an extremely ritualized ceremony where followers proceed in slow procession around an altar, repenting of the sins and praying for blessings from heaven. In the day, two additional ceremonies were held which were significant for more pious followers who, after committing to longterm study and self-cultivation, want to eventually become”lay Taoists” – spiritual adepts who dedicate themselves to following the Tao, but aren’t members of the clergy.

The party was meant to expand the influence of Taoist culture, notably by bringing more young people to watch and take part in this traditional festival. Because of this, the thoroughly planned event was filled with fresh interpretations.

Among the most surprising innovations lay in the organizers’ repurposing of traditional iconography. In contrast to traditional images of Laozi – which tend to depict him as an elderly, ethereal, sage-like figure – the predominant image at the City God Temple was an anime-style illustration of Laozi as a baby, his hair drawn back into a bun, naked as the day he was born.

The icon’s artist, the Taoist priest Wang Minyuan, told me that the infant Laozi is, in fact, a very important part of Taoist iconography. It has its origins in the Eighty-One Transformations of Lord Lao – an illustrated religious text – in which it represents the beginning of the universe. In addition, the image of a child reflects the Tao Te Ching’s veneration of newborns, who symbolize the purity and sincerity of ancient times. Returning to a state of primordial communication with the Tao is the ultimate aim of those who practice Taoist self-cultivation – but that’s not to say representations of this ideal cannot also be updated for modern followers.

The event compellingly mixed modern-style iconography with much more traditional paraphernalia. Organizers erected a shrine to the Holy Infant and a further altar in honor of the Sovereign of the Void, a Taoist celestial worthy. The former harkened back to the tradition of sacrificing to Laozi during the Han Dynasty. The shrine was draped in a purple coverlet that joined together like curtains in the front, with a statue of the infant Laozi housed within.

The latter followed the ancient style of the Tang and Song dynasties, featuring outer, middle, and inner altars. Believers gathered to pay their respects at the outer alter, with a view of the religious accoutrements laid out on the middle altar. Finally, the inner altar was dedicated to spaces for the high priest, the abbot of the temple, and the other religious masters to perform Taoist rituals.

The planners’ intentions behind committing and constructing to these special altars were clarified by Taoist priest Tao Guanjing. The altars’ reappearance reflected the ongoing revival of the Taoist belief in spontaneity, he said. Taoist priests and adherents were invited to interact with one another during the ceremony, as a means of restoring the long-lapsed connection between the temple clergy and the congregation. Together, they gave free reign to the concept of universal salvation through communing with the Tao.

Interestingly, the entire event was broadcast live on internet giant Tencent’s Taoism channel, an online TV station that, alongside Buddhist and Confucian sister channels, aims to popularize Chinese traditional religion via the web. This was a historic first for a Shanghai-based Taoist ceremony. On the ground, three camera operators filmed the event in real time, beaming full, detailed coverage of the ceremony to audiences at home and abroad. Statistics showed that 630,000 viewers tuned in to watch the morning mass, a number that grew to 740,000 by the end of the day.

Throughout the broadcast, a senior Taoist of the Shanghai City God Temple, Li Daqian, offered commentary on the ceremonial happenings, explaining in exhaustive detail each stage of the event as it proceeded. The effect was to give audiences at home insight into the rituals playing out on their screens, challenging the idea that Taoism is impenetrable, irrelevant, or irreconcilable with modern life.

Outside of the specialized Taoist ceremonies, pilgrims and tourists to the City God Temple could hang talismans bearing their personal wishes for the future, as well as eat local pastries purportedly infused with the energy of the Tao. These activities reflected a deep-seated commercial aspect of Taoist festivals, many of which historically developed into temple fairs with distinct regional customs. The Laozi Fair at Chengdu’s Qingyang Palace, located in southwestern China’s Sichuan province, takes place alongside a local flower market; in the same vein, the treats on offer at the Shanghai temple fair added to the sense of community participation.

Combining the traditional with the modern has long been a challenge at the heart of Chinese Taoism; indeed, it is a difficulty that confronts practitioners of all forms of Chinese traditional culture. For me, the mass was largely successful: The organizers captured much of Taoism’s basic spirit through their adaptation of ancient classics, and revitalized the ceremonies of the Tang Dynasty – a golden age of Chinese culture – for a contemporary audience. They promoted orthodox Taoist culture while utilizing modern online media, keeping their eyes trained on the preferences of today’s young people and working hard to create a “Taoist Christmas” that everyone could enjoy.

Be the first to post a message!