Selkies: The Loving Mothers Of Northern Seas

Selkies: The Loving Mothers Of Northern Seas

Amorous, affectionate and affable, Selkies are the hidden gems of sea mythology. Gentle spirits who prefer dance in the moonlight over luring sailors to their death, Selkies are usually overlooked by mythological fans for the more enthralling forms of mermaids or sirens. Nevertheless Selkies play an important role in the mythology of Scandinavia, Scotland and Ireland. Their myths are romantic tragedies, a frequent motif for land/sea romances, but it’s the Selkies who suffer rather than their human spouses and lovers. While the stories of Selkies always start with a warm and calm “once upon a time”, there are no true happy ending for the stories of Selkies–somebody gets his/her heart broken.

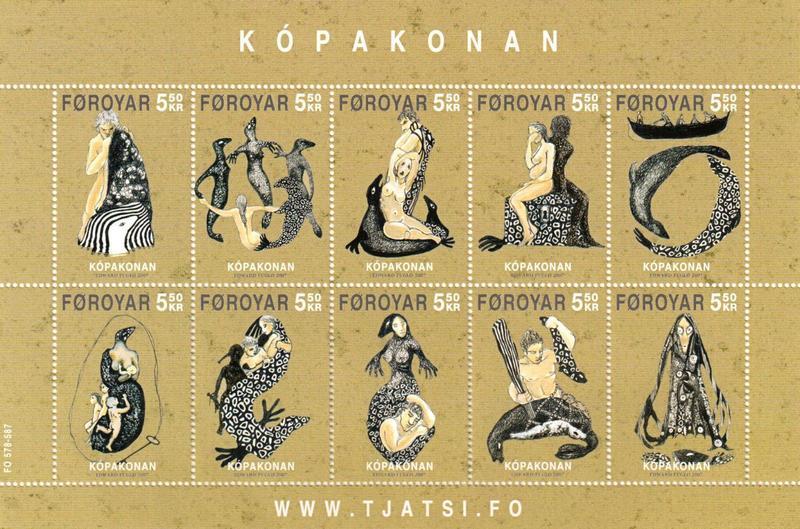

The mythology of selkies is very similar to that of the Japanese swan maidens, although historically it seems that the stories of the swan maidens predate the western tradition. Selkies can be men or women, but are seals while in the water. What distinguishes them from mermaids (besides the choice of animal) is they undergo a complete body transformation upon arriving to shore: they don’t only change seal tails into individual legs, but instead completely shapeshift from the sea animals to a human. This can be accomplished by dropping their seal-skin when they come to land. Selkies are mythological creatures from Irish, Scottish (particularly in Orkney and the Shetland Islands) and Faroese folklore, but there’s a similar tradition in Iceland too.

Described as unbelievably handsome and lovely, Selkies take the role of both prey and predator. Those who willingly return to land frequently seek those who are already disappointed in their everyday lives like the wives of fisherman. It seems more prevalent in myths the”predator” Selkies are usually the males, as stories suggest that the men more frequently find lonely humans; however, in addition, there are variations where human women decide to summon male Selkies to the coast by sending seven tears into the sea. Selkies can only stay in the presence of people for a brief period of time, then need to commonly wait seven years to reunite. This rule is broken, however, as soon as a Selkie is forced to remain a human without his/her consent.

Male selkie ( no-maam. blogspot.com )

Another way in which Selkies eventually become a part of human life is when their seal skin is stolen. These stories most often happen to feminine Selkies, creating the role of”prey” as mentioned previously. It’s not unusual in myths for Selkies to come ashore and change into people for pleasure, and it’s frequently during this time (when the skin is left unattended) that human men steal the female’s skin.

After a Selkie is no longer in possession of his/her skin, the Selkie is beneath the hold of the individual –most frequently depicted as a marriage. Interestingly, Selkie girls are extremely good wives, but no matter how joyful a Selkie is on land, or the number of kids he/she beget during their period on the surface, after a Selkie recovers his/her lost skin, the Selkie instantly returns to the sea without looking back. Paradoxically, various tales also portray the half human kids inadvertently finding their parent’s missing skin and returning without being conscious of the consequences.

One quite infrequent narrative of Selkies shows what occurs when a Selkie chooses to come back to the sea. It seems, according to a narrative from the Faroe Islands, that upon making this decision, the Selkie isn’t able to return to his/her former life if the Selkie wanted to. An abridged version of the tale refers to a human husband drifting right into a treacherous storm, saved only when his Selkie wife retrieves her skin and rescues him as a seal from certain death. Though this narrative suggests a true love between the Selkie wife and her husband, her donning of her seal skin will prevent her from taking part in the human world . This is just one variation, of course, and consequently is contradicted by other mythologies, but it’s pertinent to the narrative of Selkies since it shows that human/Selkie marriages are not hollow.

Selkies are much tamer and much more gentile than their mermaid and siren counterparts, and it’s probably because those cultures that believed in Selkies lived quite near the sea and, in ways, the edges of the world. To these civilizations, the sea has been equally wild and bountiful at the same time. It isn’t unreasonable to presume that the essence of the Selkies has remained tame throughout their legends since the sea was a source of survival for the Scandinavians and Scotsmen who believed in them. While Selkies are somewhat less dominant in cultural conventions today, they ought to be appreciated for their preference to love rather than harm people. It’s more pleasant to image a Selkie mother watching over her children from the sea, compared to a enchanting mermaid planning her next underwater vanquish.

Bibliography:

Briggs, Katharine. 1976. An Encyclopedia of Fairies. Pantheon Books: New York.

Matthews, John and Caitlin. 2005. The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures. Barnes & Noble Publishing.

Monaghan, Patricia. 2009. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Arrow Books: UK.

Spence, Lewis. 1948. The Minor Traditions of British Mythology. Rider and Company: Towrie, Sigurd. “The Selkie Folk.” Orkneyjar: the heritage of the Orkney Islands. Accessed 1, August 2016. http://www.orkneyjar.com/folklore/selkiefolk/

Williamson, Duncan. 1992. Tales of the seal people: Scottish folk tales. Interlink Books: NY.

Be the first to post a message!