Magic Moments: A Review of 'Grimoires: A History of Magic Books'

Magic Moments: A Review of 'Grimoires: A History of Magic Books'

In this exploration of grimoires, books of magical knowledge, Professor Davies covers an eye-wateringly wide range of material, from clay tablets in ancient Babylonia to Buffy the Vampire Slayer (below). He makes the bold claim that to know the history of grimoires is “to understand the spread of Christianity and Islam, the development of early science, the cultural influence of print, the growth of literacy, the social impact of slavery and colonialism”.

Those brought up with the view that magic is the preserve of primitive people who progress with civilisation to religious belief will be surprised to find how closely religion and magic were always linked in their written manifestations. One example comes from colonised peoples, who believed the Bible was the occult source of the power of the whites. A widespread conspiracy theory grew up - reported from Africa, South America and the South Pacific - that the Europeans spreading Christianity were deliberately withholding some of the magic in the Bible, in order to keep them in a state of subjugation.

Such beliefs in extra-biblical magic are part of a tradition stretching back at least to the fourth century. The characterisation of Moses as a great magician claimed that only the first five books of divine teaching made it into the Bible; other secret texts circulated as grimoires - and still do. There was no shortage of court cases in the first years of the 20th century in the US citing the maleficent use of the seventh book of Moses for removing unwanted spouses and former friends in the so-called “hex murders”. There were warnings also to the user: if a book’s instructions were not strictly followed, it could induce madness, and merely looking at some of its incantations could make one go blind. Believers were moved to terror by the thought of the even more esoteric eighth and ninth books of Moses, with presumably no end to the potential horror of numerical progression.

The democratisation of high magic in the Renaissance meant suddenly everyone was at it, and the demand grew for books giving the runic farting spell; the use of candles made from the fat of a hanged man; and practical manuals for causing rain, seducing women or for making enemies mute with “a weezle’s tongue, dried and worn in the shoe”.

Criminal records show how the widespread use of magic was exposed in the plot to assassinate Louis XIV by a cabal of sorcerers who were purveyors of poison to the palace (as well as of cosmetics, breast enlargers and the sanctimoniously named “angel makers”, which were abortifacients).

Believers were highly resistant to challenge. The great sceptic Reginald Scot’s exposé The Discoverie of Witchcraft of necessity gave examples of spells but was then used as a repository of ancient lore by charm merchants who recycled its research. When a French government official defiantly laid his hand on a book, whose mere touch was supposed to conjure the devil, the non-appearance of Lucifer was considered evidence of the official’s skill as a secret magician. Sometimes the seekers were tricked: Benjamin Franklin’s spoof astrological guide Poor Richard’s Almanack was circulated as the genuine esoteric article, but in fact gave a rationalist message within the binding of a grimoire.

Paradoxically, as capitalism triumphed and the world became more materialistic, esoteric knowledge flourished in the occult revival. In the US, the birthplace of advanced capitalism, one grimoire even founded a religion. In the 1820s farmer Joseph Smith was employing the usual talismans and peep-stones to seek buried treasure in Wayne County, New York. He is said to have discovered two golden plates; the translation of the esoteric characters on them was published as The Book of Mormon. With this guide, Smith founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

The pulp novelist HP Lovecraft wrote of a fictional grimoire, the Necronomicon. With no assistance from Lovecraft, versions of the work with bogus genealogies linking it to Mesopotamian sources then appeared. It is this blurring of fiction and folklore that fed the modern obsession with witches, from the “satanic abuse” of credulous social workers to Harry Potter, television series such as Charmed and the burgeoning popularity of Halloween as a festival.

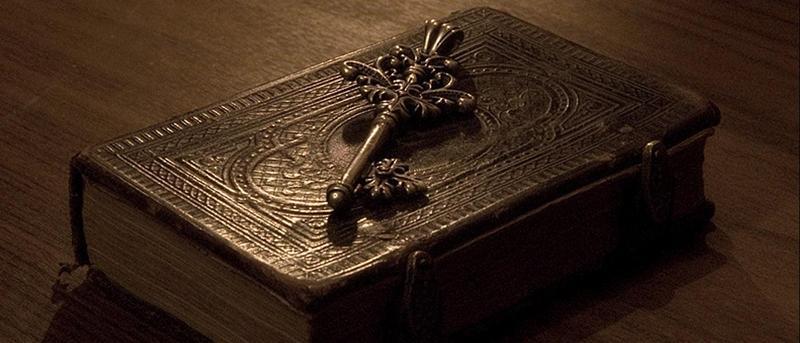

In this erudite and entertaining addition to book scholarship Davies makes a convincing argument about the resilience of books, with their enduring ability to shape the modern age despite the addition of electronic alternatives. In keeping with this spirit, Grimoires is a beautifully produced, surprisingly inexpensive book with black end papers and suitably antique illustrations, though a larger type size would have been welcome, for the benefit of older scryers.

By Had Adams/The Guardian

Be the first to post a message!