Freemasons members may have shaped Britain's history

Freemasons members may have shaped Britain's history

For centuries, they have shrouded themselves in secrecy. So murky is their history, their origins are opaque even to themselves.

Their rituals are conducted in private, with members swearing a melodramatic oath that threatens them with ‘having my throat cut across, my tongue torn out by its roots and buried in the rough sands of the sea at low-water mark’ should it be violated.

But what’s inspired endless rumour and speculation is how the influence of this shadowy organisation reaches to the very heart of the Establishment — to senior politicians, high-ranking military men, diplomats and spies, chief constables and scientists.

They are, of course, the Freemasons. And according to a secret membership archive open to the public for the first time, the number of leading figures in British history is likely to be even greater than conspiracy theorists would have you believe.

The newly released list of two million names includes at least five kings (most recently Edward VII, Edward VIII and George VI), the present Duke of Kent, statesmen Winston Churchill and Lord Kitchener, military genius the Duke of Wellington, authors Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Conan Doyle, England manager Sir Alf Ramsey, the explorer Ernest Shackleton, the scientist who discovered penicillin, Sir Alexander Fleming — and flamboyant playwright Oscar Wilde.

According to estimates, there are 250,000 Masons in Britain and six million Masons worldwide. They may be relatively few in number, but they wield considerable influence across all sections of society.

The very mention of the Freemasonry — one of the world’s oldest and biggest non-religious organisations — is guaranteed to prompt a rash of contradictory reactions. Defenders rightly point to its tradition of charity fund-raising and official websites promote it as an ‘enjoyable hobby’.

Indeed, the website of the United Grand Lodge of England recommends it for ‘making new friends and acquaintances’.

But do such close friendships lead to too much power being vested in individuals who favour fellow Masons in everything from promotions to business deals? Membership lists are notoriously hard to get hold of, making it difficult to detect corruption.

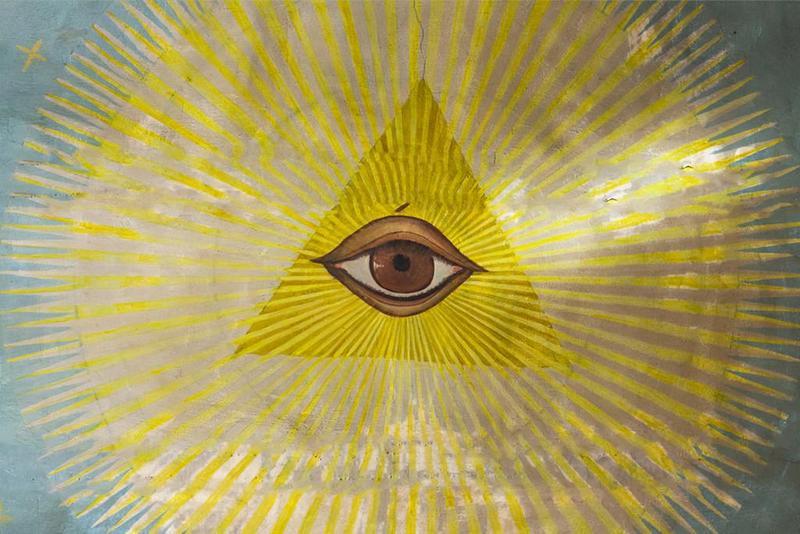

Others believe the Freemasons, with their arcane ceremonies, secret handshakes, lambskin aprons, embroidered sashes and gold rings, and their ornate symbols — the square, the compass — are more the stuff of pantomime.

There aren’t many ‘private societies’, after all, whose members swear an oath blindfolded, bare-chested, with nooses around their necks and a dagger to the heart — and with the left trouser leg rolled up.

Yesterday, however, proved to be a field day for those who claim the Freemasons are a force not for good, but for bad.

Working from the complete English Masonic membership records dating from 1751 to 1921, genealogical website Ancestry has established that at least five people associated with the official inquiry into the sinking of the Titanic were Freemasons. It argues this may have influenced the findings, which exonerated most of the key figures involved.

It was also claimed yesterday that one of the most notorious murderers in British history may also have been a Mason.

According to a new book by Bruce Robinson, the writer of the cult film Withnail & I, none other than Jack the Ripper was a Freemason. It begs the question whether his identity was covered up, allowing him to carry on with his murderous campaign in which five women died.

The websites of modern-day Masonic lodges, some of which pay at least lip-service to being less secretive, talk virtuously of how it is frowned upon for a member to use his Masonic status for a career leg-up.

But down the centuries, their clandestine activities have — however unfairly — convinced many that as a fraternity they were collectively up to no good.

There have been glimpses of serious wrongdoing. The late Yorkshire architect and Freemason John Poulson was jailed for seven years after being found guilty in 1974 of bribing public figures to win contracts.

The judge called Poulson an ‘incalculably evil man’ and his conviction precipitated the 1972 resignation of Conservative Home Secretary Reginald Maudling, who had been a director of Poulson’s firm.

Freemasons’ origins in Britain seem to date back at least to the late 14th century. The Freemasons believe their roots — and their very name, and hence their symbols — lie in the masons who built the great medieval cathedrals, such as Salisbury, started in 1220.

Certainly, by the end of the 17th century, there were several lodges — as the individual Masonic societies are known — dotted around the British Isles, with at least seven in London.

It was in the capital that four lodges came together in June 1717 to form the first ‘Grand Lodge’, which published its first minutes and constitution in 1723.

Within a few decades, the Masons started to attract to their number some of the most influential men in London society, including members of the Royal Society, artists and writers such as William Hogarth and Alexander Pope, and members of the aristocracy, right up to dukes.

In 1776, the Freemasons opened a sumptuous hall as their Grand Lodge in Great Queen Street, Central London. This was replaced in the Thirties by the monolithic Freemasons’ Hall.

Their web of influence spread throughout the country and society. Some lodges met at taverns and inns — and today, many taxi drivers, plumbers and even dustmen are Masons. There are two lodges for women Masons.

While the Freemasons insist their private meetings do not mask anything nefarious, that was not universally so. In the late 18th century, for example, a lodge in Brentford was accused of plotting to kill George III. The conspiracy did nothing to deter his two sons, George IV and William IV, from becoming Masons.

Freemasonry really took off in the wake of the two world wars. In the three years after World War I, 350 lodges were established, and in three years after World War II, nearly 600 were set up.

The Freemasons claim this was due to an increased number of men ‘who wanted to continue the camaraderie they had built up during their war service, and were looking for a calm centre in a greatly changed and changing world’.

That may well be so, but it does not answer the question that many have asked about their activities for nearly three centuries: who benefits from whatever it is they do? The Masons themselves or is it society at large?

The Freemasons do not deny that much of their generosity is allocated to themselves and their dependants, often in the forms of healthcare and education. But there is nothing wrong in creating a society for mutual benefit.

And good causes benefit. Each year they give £1 million to the Royal College of Surgeons ‘for the betterment of mankind’. Most members are surely honest, decent and altruistic.

But it is hardly surprising, given the closed way members go about their business, that cynics maintain some Masons’ primary ambition is to give each other favours and backhanders, turn blind eyes, wave through promotions, sign contracts and bestow all manner of benefits not available to others.

by Guy Walters for The Daily Mail

Be the first to post a message!