Why Sex (Really) Matters

There is no more important topic in the social sciences than sex. The truth of this assertion is linked to two indisputable facts: sex often produces babies, and babies are not born blank slates. Though remnants of the Tabula Rasa myth still haunt the periphery of developmental science, a large portion of the scientific community (and increasingly, the public) has finally squared with the fact that human individuality is partly governed by genes. Put differently, part of the reason people differ from each other on measures of personality, intelligence, and temperament is because they are genetically different from one another. Because people vary genetically, our choices about who to have children with are immensely important, both for our children, and for those who will share the planet with them.

Yet for many, recognition of just how critical reproductive decisions are seems to shift into gear only after a child is conceived. At that point, many of us are concerned with the mother’s ability to secure an abortion safely and without duress (within certain parameters), if that is what she ultimately desires. If her desire is to carry the pregnancy to term, yet not raise the child, adoption agencies are in place to make the appropriate arrangements. Networks of foster care providers ensure that children are cared for, in the event that parents are unwilling or unable to offer care themselves. Should the state need to remove a child from a home, mechanisms are in place for that as well.

Nonetheless, we have failed to grasp — or openly discuss — the deeper consequences of having children. If we were born as blank slates, the qualities of our parents (their predispositions or temperaments) would be largely irrelevant so long as they provided an appropriately safe and enriched environment. We seem to persist in the incorrect assumption, however, that parental influence begins at birth, not conception, and lays down its true marks as the child ages. But ever since Francis Galton — a pioneer of statistics and relative of Charles Darwin — suggested using twins to study the heritability of traits, scientists have had a sense of how parents influence their children’s personalities even before they leave the womb.

Indeed, for as long as we’ve intentionally bred plants or animals in an effort to either exaggerate, or mute, certain characteristics, people have had clear awareness of the fact that some traits are transmitted (biologically) from parents to children. Only more recently, though, have we fully grappled with what this means for human beings. Well over five decades of behavior genetics research have revealed that practically every psychological and physiological outcome is, to some extent, heritable. The reality of heritable variation does not mean that parents pass along, with perfect fidelity, personalities and temperaments to their children. The heritability of these traits, however, does mean that certain propensities can cluster in families, owing not only to social transmission, but also to genetic transmission.

The heritability of physical and psychological traits is not generally disputed among behavioral geneticists or evolutionary biologists. Indeed, the very equations we use to forecast the effectiveness of breeding programs depend partly on the heritability of traits, and those equations apply as much to people as they do to plants. It is no great secret why commentators and scientists dutifully avoid this topic, though. To discuss breeding in any organism besides humans is merely academic, but to toss Homo sapiens into the mix is to harken back to the horrors of eugenics. Fear of this topic (and disgust towards it) is understandable. At the same time, it seems reasonable to try to parse out why people initially thought it important to be concerned with human breeding, and also how that concern was mistakenly translated into atrocity and murder.

Eugenics — where it came from, and what it got right

Broadly speaking, eugenics refers to any attempt to consciously harness the power of reproduction to influence the traits of future people. Put this way, it is innocuous, and something many of us do already by thinking carefully about whom we want to have children with. Long-term mate selection, for the most part, is far from haphazard.

Part of what motivated Galton to study twins in particular, and heredity in general, was his sense that for the first time in recent history, developed countries were creating the conditions for people with less desirable traits to leave more surviving offspring than those with more desirable traits. The main idea, popularized in the opening scene of Idiocracy, is that ambitious and educated people who want to make a mark on the world often reproduce later in life, and deliberately have fewer children than those with less lofty ambitions or opportunities. Meanwhile, Galton thought, people who are not especially ambitious or successful or prudent, tend to have more children.

Galton also suggested that welfare programs and medical advances in wealthy countries tend to preserve people who would not otherwise survive and reproduce. Over the last century or so, these observations have become even more salient as everything from food and health care to education and housing have been made freely available to parents. This is illustrated by a recent case of a thirty-year-old man who has had 22 children by 14 different women, despite his inability to support his children. Putting these ideas together, and reflecting on his cousin Francis Galton’s work, Charles Darwin worried that:

the very poor and reckless, who are often degraded by vice, almost invariably marry early, whilst the careful and frugal, who are generally otherwise virtuous, marry late in life, so that they may be able to support themselves and their children in comfort.

Darwin recognized our moral obligations to help the poor. But he also worried that people in the modern world:

do our utmost to check the process of elimination… we institute poor-laws; and our medical men exert their utmost skill to save the life of every one to the last moment… Thus the weak members of civilized societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man.

Darwin’s language shocks our modern sensibilities, and that is understandable. As the eminent biologist John Maynard Smith has said:

Improved medical and social care make it possible for people who in the past would have died to survive and have children. Insofar as their defects were genetically determined, they are likely to be handed on to their children. Consequently, the frequency of genetically determined defects in the population is likely to increase. I think we have to accept the fact that there is some truth in this argument, but it is a little difficult to see what we should do about it.

The key point in Maynard-Smith’s statement has to do with heritability. If genes played no role in shaping our characteristics, then the qualities of parents would be no real concern. All that would matter is the rearing environment of the child. Providing a more concrete example, violent forms of antisocial behavior are moderately-to-highly heritable. Importantly, criminal offenders tend to father more children with more partners, and yet are far less willing to invest much in their care (compared to non-offenders). Taken together, it is perhaps not surprising to observe the concentration of crime in certain families. And more generally, it is reasonable to assume that life in these families is less than ideal for the children born in to them.

Why we should be skeptical of eugenic policies but embrace eugenic principles

That said, there is an obvious corollary to Maynard-Smith and Darwin’s points. Diseases that might have eradicated many of us — even something as ordinary as poor eyesight — are dealt with (often easily) by modern medicine. This has been overwhelmingly good for society. As a result, most people are viscerally opposed to eugenics, and with good reason. The word “eugenics” will forever be associated with mass sterilization and death camps in Nazi Germany. It should go without saying that any sane person would vehemently oppose the policies that led to the greatest human tragedy of the twentieth century. The Holocaust can be traced to the morally abhorrent and scientifically erroneous beliefs of its chief architect, Adolf Hitler, who maintained that there was a “struggle for existence” between the great races, and that Jewish success in particular was a threat rather than a boon to the German people.

The eugenics movement that began in England with Francis Galton, one of the greatest scientists of the nineteenth century, essentially ended in Germany when pseudo-science serving a repugnant political ideology was used to justify mass murder. But some of the moral principles that supported the original eugenics movement remain compelling, even if we are rightly skeptical of using the power of the state to achieve eugenic goals.

Just a few years before Galton coined the term “eugenics,” John Stuart Mill popularized the classical liberal view that all self-regarding actions should be legally permitted, but actions that produce significant harm to others might be legally restricted, or at least discouraged via social pressure. Despite a strong presumption in favor of liberty, Mill defended laws that require prospective parents to demonstrate their ability to take care of offspring before having them. “Such laws,” he argued:

are interferences of the State to prohibit a mischievous act—an act injurious to others, which ought to be a subject of reprobation, and social stigma, even when it is not deemed expedient to superadd legal punishment.

Mill also criticized the:

current ideas of liberty, which…would repel the attempt to put any restraint upon inclinations when the consequences of their indulgence is a life, or lives, of wretchedness and depravity to the offspring.

Mill’s argument suggests that although we should be wary of coercive eugenics, there is a clear moral rationale for using social pressure, and in extreme cases, legal sanctions, to prevent parents from knowingly giving birth to children that they’re not in a position to care for, or might be in a position to actively harm. This rationale also suggests that parents with heritable conditions that are likely to undermine their child’s well-being should be subject to the same scrutiny as people who abuse, neglect, or otherwise harm their children once they are born.

One of the lessons we can learn from some of the more heedless proponents of eugenics is that government agents are not always in the best position to decide who should give birth and who should not. But some governments are in a position to set and enforce general rules that tend to increase the extent to which individually rational reproductive choices are also collectively beneficial. Generally speaking, for any conceivable rules governments might set, they should use the least restrictive alternative for achieving the desired result. For example, if supplying information to mothers about genetic and environmental risks achieves the same result as forcing women not to eat certain foods or reproduce with certain people, we should promote informed choice rather than using force.

One proposal previous eugenicists have made is to pay people with undesirable qualities — such as extremely low intelligence, or poor impulse control — not to reproduce. William Shockley went as far as to say that the state should pay people not to have children along a graduated scale in proportion to how many points below the mean IQ (100) they fall. This proposal has serious problems that likely doom it to failure. Make no mistake, intelligence is a crucially important trait for living a successful life, but it is far from the only trait that matters. Qualities like compassion, empathy, and creativity are important for human flourishing, and for treating other people with respect. Policies like these, moreover, might lead to the manipulation of IQ test results by corrupt bureaucrats. Finally, IQ scores are at least partly affected by environmental factors in ways that are not well understood as of yet, a point that should not be overlooked (even if these effects are often exaggerated by blank slate enthusiasts).

Instead of Shockley’s proposal, one might contemplate the feasibility of a parental licensing exam, one that measures a broad array of characteristics that include intelligence, along with a host of relevant personality and behavioral traits. Even a moment’s contemplation, of course, reveals that devising such a test is challenging. Yet don’t we already extensively evaluate adoptive and foster parents across an array of parental fitness indicators? Why do biological parents get a complete pass in this regard? There might be good reasons, but we should be prepared to consider what they are, and clearly articulate them, before rejecting this idea out of hand. Still, this proposal is likely to offend many people’s sensibilities, and is clearly fraught with potential problems. If some version of it were workable, we would have to set the bar low enough that only extreme cases were sifted out, and we would want to allow people multiple opportunities to pass it in order to minimize the probability of bureaucratic corruption or error influencing the outcome.

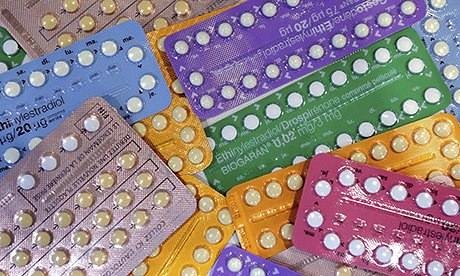

A more promising and less restrictive eugenic policy would be for states to subsidize contraception. This may help increase the autonomy of poor women, especially in developing countries where women have little control over their reproductive cycle because they cannot own property or work outside of the home without the permission of men. At the risk of sounding too speculative, assuming also that a viable contraceptive for men is invented (one that is sufficiently benign in the side effects it might induce), then it might be a reasonable idea for governments to subsidize its widespread availability at an affordable cost. In The Pivot of Civilization, the founder of Planned Parenthood, Margaret Sanger, advocated making birth control pills more widely available for exactly these two reasons. She saw the ability of reliable contraception to liberate women and enable them to make better choices about who fathers their children.

Another proposal for increasing the extent to which parents produce children with the best chance of the best life is to promote informed choice by making information about genetics more widely available, and enabling parents to use this information. Most people simply don’t understand, and don’t have time to understand, the body of research coming out of genetics labs. But governments can try to ensure – by subsidizing or mandating genetic education – that prospective parents have a better sense of the risks and benefits associated with selecting partners, or choosing the sperm or eggs they use to create children.

Some of this would have to start early, long before people think about selecting partners and having children. This sort of careful consideration of how our reproductive choices influence future people will require a sea change of public opinion, since many people still roll the genetic dice when they decide to have kids. In fact, about half of all children born in the United States are an unintended byproduct of sex, rather than a conscious choice.

Ultimately, assuming genetic engineering emerges in the next century, the availability of cheap and accurate genetic information will become increasingly important (as will the need for it to be accessible in fair and equitable ways). As contraception becomes more affordable, and technology for screening and engineering embryos becomes feasible, we may begin to treat sex and reproduction as two things we do for completely different reasons.

by Jonny Anomaly and Brian Boutwell/Quillette

Be the first to post a message!